Is there a border?

The Reunification was a change of borders, but what is a border really?

Today we call the border change in 1920 'The Reunification'. It gives the impression that the new border was as natural as a ridge or a stream.

But borders are a result of narratives, language, culture and state formations. It is people - not nature - who create borders. We set up border posts and then we tell each other that what is on this side of the border is one thing, and what is on the other side is something else - often something completely different.

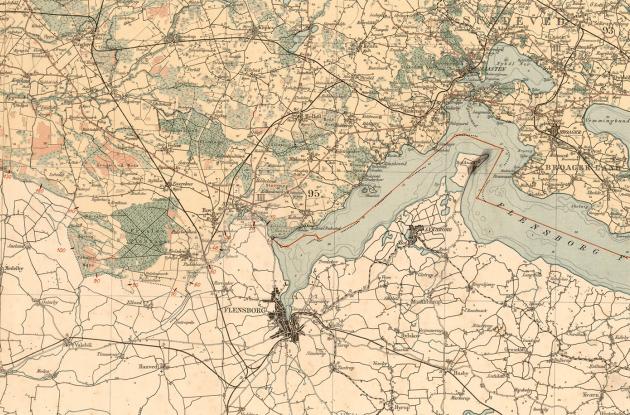

Since the end of the 19th century, we have even gone so far as to let borders determine what we identify as. Are we Danes or Germans? Well, we can start by looking at the map. Do we live north or south of Padborg? It was World War I that pushed that particular idea. The borders of the new Europe were drawn by asking the people: “who are you?” and were then determined according to the results. The same happened in Southern Jutland.

But the reality is complex.

Just as people can decide that now this ridge or this stream constitutes a border, so people can decide to feel German or Danish - no matter where they live. They can decide that it does not matter at all whether they are German or Danish. It is perhaps more important whether you are a Schleswiger, a worker or a woman.

They can, if enough people agree, decide to have open borders, or close the borders because they are afraid of disease or of those who do not look like themselves. They may decide to move the border to another ridge or a new stream - even if they do not all agree on the move. It all creates some very special circumstances in border regions. Circumstances that are also evident in Southern Jutland.

Photo: Henrik Frandsen

Love knows no bounds

85-year-old Inga Rasmussen from Tønder and 89-year-old Karsten Tüchsen from Süderlügum just south of the border have known each other for roughly two years. Before the corona crisis closed the border, they visited each other every day. Now they visit each other at the border barrier every day instead. They must not cross it as the border is currently closed, but their love for each other will not fade whether the border is open or not.

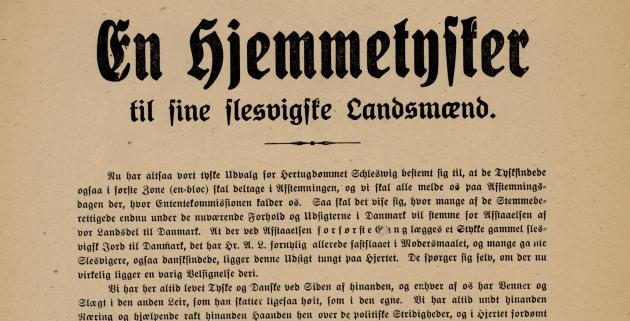

The fear of separation

Photo: Ophav ukendt

When we talk about the Reunification, we sometimes forget that it was also a separation. Schleswig had been an entity since the Middle Ages. At the Reunification, family and friends were parted by the new border. Some came to Denmark, others to Germany. In the pamphlets distributed in the time leading up to the polls, this was a fear one could play on. Here, a so-called "home German" encourages Danes to vote for Germany in order to maintain the unity of Schleswig. He fears that the Danes:

"dislike our old language and would immediately seek to transform us into Copenhageners."

Who am I?

Photo: Holger Damgaard

For some, the "South Jutland question", as it was called, was not the most important thing at the time. The labour movement was not interested in national issues. Here you were a worker first, a Dane second. It did not make sense to discuss how large a part of Schleswig should belong to Denmark when the most important question was: who owns the means of production. In Copenhagen, the Syndicalists led the demonstrations in connection with the Easter crisis .

On Mediestream you can read the Syndicalists' magazine "Solidaritet".

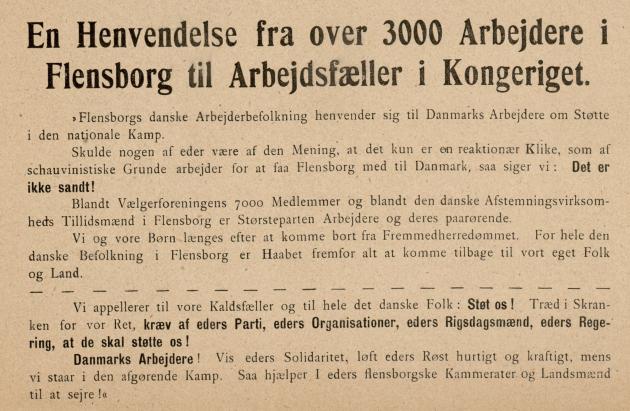

Photo: Ophav ukendt

In Danish-minded circles, people were fully aware that Danish workers did not necessarily consider the struggle for Flensburg as important. In a pamphlet, 3000 workers from Flensburg address their colleagues north of the border and hope that they will support "the national struggle".

That which gathers and that which separates

Photo: Ophav ukendt

In Denmark, the myth arose that the coffee spread in Southern Jutland was a peculiarity of the Danish-minded North Schleswigers. The peculiar thing, though, was mostly that the Danes wanted to bring their coffee tables into their assembly halls for the spread. Both Germans and Danes had the same tradition of eating many different kinds of cakes with coffee, and in fact the tradition extended far into Jutland.

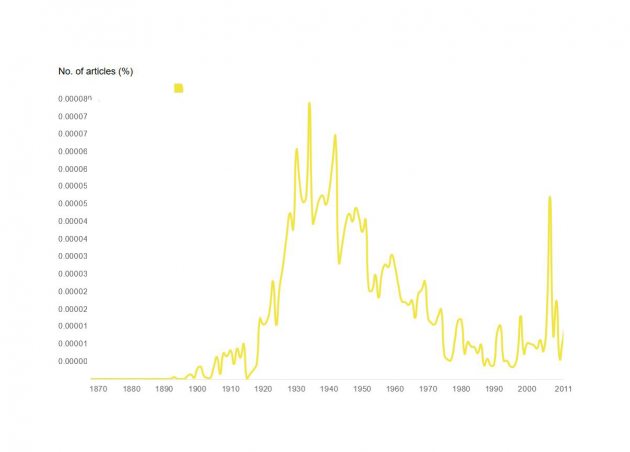

It was Danish media, among others, who solidified the idea of the coffee spread as a national gathering point. And as you can see from the graph of the use of the words "sønderjysk kaffebord" in the Danish newspapers, it was a myth that was built up in the years after the Reunification.

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek