School and the children

With the Reunification, the students in Southern Jutland suddenly lived in another country with a new king, a different language and a different mentality. They were Danish. Except those who were not.

The Reunification brought a number of large changes for the school children in Southern Jutland. Up until then, they had gone to German schools, read German books and learned the history of the German Empire.

Photo: ophav ukendt

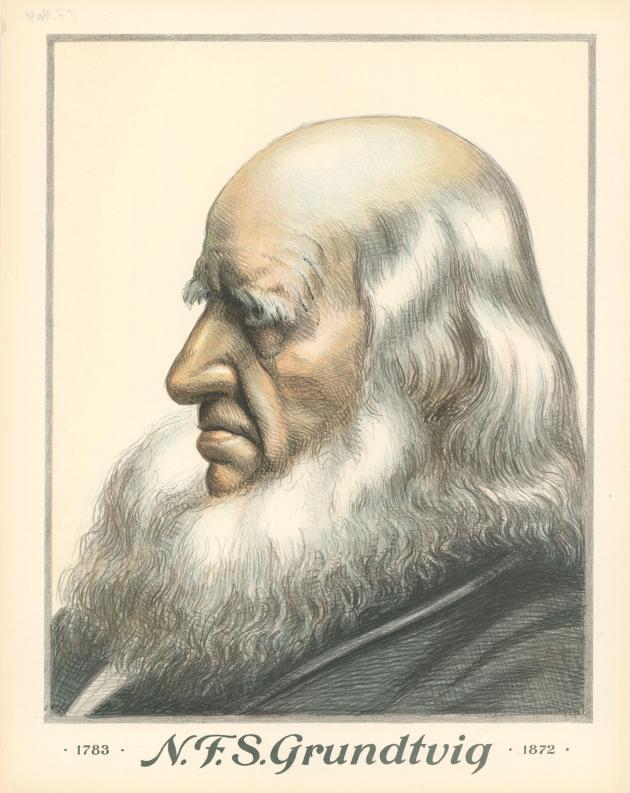

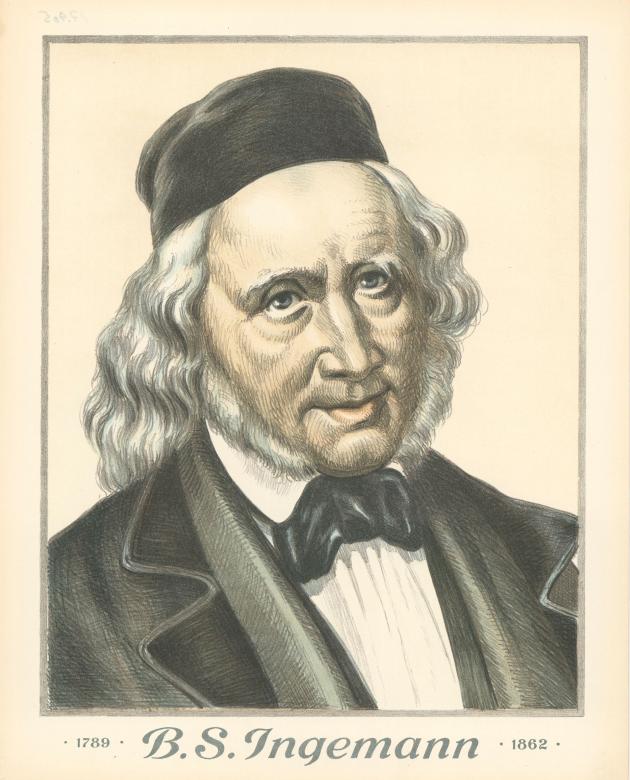

Now the language in school, the essays, and the history of the mother country became Danish, and they would no longer find Grimm and Goethe in their textbooks, but rather Hans Christian Andersen, Grundtvig and Ingemann. It was the fourth time in less than a hundred years that the school language changed in the area, so it was not unknown to the population.

Besides the many fundamental changes and the great uncertainty surrounding the future, the school children and the rest of the population were recovering from the First World War and the Spanish flu.

Since the start of the war in 1914, schooling in North Schleswig had gone downhill. Many teachers had been called to war, so the school children in the area were only occasionally taught by those who had the time, and a large part of the children had to help out at home instead of going to school because their fathers, their servants, and perhaps their older brothers had also been sent to war. In the winter, the schools had often closed because there was a lack of firewood, so the schoolroom could not be heated. In 1918-19, the Spanish flu ravaged the world, killing 50-100 million people.

Photo: ophav ukendt

When the war ended in 1918, a year and a half of a political vacuum in Southern Jutland followed. There was a shortage of teachers and no money. Germany was hit by inflation, so many could not pay their bills. Clothes, food and school books from Denmark were distributed in many of the towns and cities in Southern Jutland. It was a hard time to be a child. Many school children in Southern Jutland had big gaps in their schooling, they had relatives or friends who had died in the war or of the Spanish flu, and they were impoverished and hungry when King Christian X rode across the border to Southern Jutland on 10 July, 1920.

The School Scheme of Southern Jutland

After the Reunification, the Danish Parliament introduced the School Scheme of Southern Jutland, which was to ensure an easier transition to Danish conditions. The parents should have the right to decide over their children's schooling, including the German-minded parents, who should have the right to send their children to German schools, even though they now lived on Danish soil. Both the political and the local side wanted to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past and instead respect the minority's right to education in their mother tongue.

Photo: Ophav ukendt

With the passing of the School Scheme of Southern Jutland in 1920, the parents were given influence over the establishment of German private schools, and the parents had decisive influence on both the employment of teachers and on the supervision of the schools. Something they did not have to the same extent in the rest of the Danish kingdom.

The new minorities

South of the new border, approximately 8-10,000 Danish-minded children and adults had to agree to remain part of Germany. Roughly 1,000 children were enrolled in the Danish department of the public school, but only 239 were assessed as Danish-minded by the German authorities. The rest were sent to German schools. The lack of hospitality towards the new Danish minority increased interest in the establishment of Danish private schools.

Photo: Ophav ukendt

The German minority in Southern Jutland formed Deutscher Schulverein, the German School Association, which was to ensure the preservation and spread of the German language and culture among the German-minded in Southern Jutland. In the beginning, the vast majority of German-minded schoolchildren went to the public German school departments, but the parents quickly began to set up private German schools because they felt that there was a hidden danification process going on in the public schools through the employment of several Danish-minded teachers, and by introducing teaching materials that were German translations of Danish authors.

The school district was to remain a contentious point for minorities south and north of the border, especially in the years leading up to, during and immediately after World War II.

You can read more about this on skolehistorie. (Only in Danish).