Cultural rearmament

It was not gunpowder and bullets that won the battle for Southern Jutland. Instead, the weapons were pen and paper, road signs and burial mounds, dream visions and voter associations.

Photo: Ophav ukendt

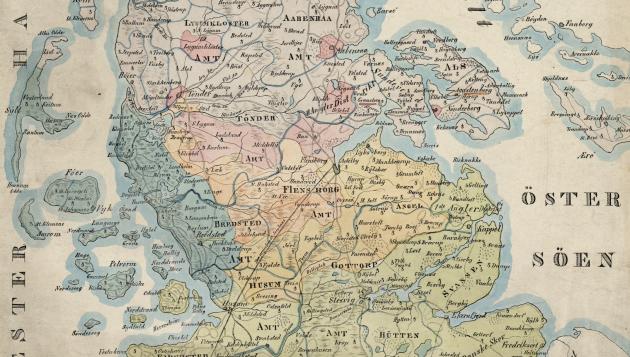

The line of the new border across Southern Jutland was decided by referendums in the early 1920s, and the national mentality became paramount in the election campaigns. The election was the result of a cultural rearmament on both sides of the conflict that began at least a hundred years earlier. Linguistic arguments and national symbols were used excessively. Mother Denmark, the Golden Horns, Dybbøl Mill and motifs from ancient times were used in a way that may seem a little thunderous to us today.

Language, culture and symbolism were used instead of cannons and cavalry in a battle for the minds and hearts of the Schleswigers. For it was the mentality of the people that could shape the new map and move the borders.

Virgin Fanny's dream visions

Photo: Thorvald Larsen

There are many myths about the seamstress Franziska Caroline Eliese Enger, who lived in Aabenraa from 1805 to 1881. She was called "Virgin Fanny", and rumour has it that she was the daughter of Christian VIII. At the age of 27, Fanny became seriously ill and everyone thought she would die. She survived, but then she began receiving premonitions.

She foresaw the outcomes of the wars of 1848-1851 and 1864. People found solace in listening to what Virgin Fanny had to tell, and broadsheets were published about her dream visions.

Virgin Fanny also foresaw the Reunification, which took place long after her death.

In her dream vision, the king rode across the border on a white horse, and when the Reunification was to be celebrated in 1920, a white horse was procured for Christian X. Virgin Fanny's prediction came true, and it gave renewed strength to the myth of Fanny's special abilities. It may be said that Virgin Fanny was honoured for the hope of reunification that her predictions had spawned among the Danes in Southern Jutland.

Read a broadsheet of Fanny's prediction. (In Danish).

The Golden Horns as a national symbol

Photo: Holger Damgaard

When King Christian X met with the Southern Jutlanders at Dybbøl on 11 July, 1920, he was presented with two replicas of the Golden Horns. The longer of the Golden Horns was found in 1639 at Gallehus in Southern Jutland. A few meters away, the shorter Golden Horn was found in 1743.

On one Golden Horn was a runic inscription. The first interpretation of the inscription came in 1865, when an effort was made to use the language 'Old Norse' instead of 'Old Germanic'. In the battle between German and Danish identity, ancient finds were used as an argument to regard Southern Jutland as old Danish territory. This is the reason why the Golden Horns - together with other ancient finds such as lures and burial mounds - were used as illustrations on appeals to vote Danish in 1920.

One border country with three languages (at the very least!)

Photo: P.C. Koch

In Denmark, the question of Southern Jutland is often reduced to dealing with language - then as now. You are either Danish or German, depending on which language you speak at home. It has never been so simple in Schleswig.

Photo: Ophav ukendt

Before 1800, language was not very important for the population's identity. Frisian, Low German and Synnejysk thrived side by side from the early Middle Ages. Around the Renaissance, High German and Danish were added, particularly as church languages.

During the 19th century, nationalism blossomed. It did not come from Schleswig, but from Kiel and Copenhagen. In this movement, language gained great importance, and there were perhaps not consideration for the complex conditions of the border country. Many Schleswigers had spoken the language that was convenient in the situation in the past. People may have spoken German in church, but Danish at home - or vice versa.

Photo: Ophav ukendt

The logic of nationalism required the Schleswigers to choose one language and one identity. Many Schleswigers chose to follow the language they were accustomed to speaking in church. In South Schleswig, German became dominant, while a clear majority in the countryside in North Schleswig gravitated towards Danish. This mostly mirrored which language was used in church.

In the northern Schleswig cities, such as Aabenraa and Haderslev, the national sympathies were divided the most. Here two languages had been spoken in church since the 16th century. Most of the bourgeoisie went to the German church service, while people of a more common background went to the Danish service.

The signage war

For the German minority in Southern Jutland, Haderslev is not called Haderslev but Hadersleben. Aabenraa is not Aabenraa, but Apenrade, Tønder is not called Tønder, but Tondern, and so on. The question of getting the German names under the Danish ones on the city signs regularly arises, but so far not a single municipality in Southern Jutland has chosen to put up bilingual signs.

Photo: Max van Gellekom

They gave it a try in Haderslev in 2015. It caused major protests, and a few days later, the sign had been knocked down. It never came up again. South of the border, the attitude towards bilingual signs is different and there are signs with Low German, Frisian and Danish "subtitles".

Tondern became Tønder

Language thus became essential for the notion of where you belong. The poet Johannes Buchholtz (1882-1940) captured it with his poem "Paa Tondern Station" the night between 16 and 17 June 1920. A small event among the many great festivities of the Reunification. Danish railwaymen quietly changed the signs at the station, transforming Tondern into the Danish Tønder. In English:

Not a Saber rattled

through the nocturnal Peace,

one only raised a Ladder

and took down some signs.

It was not a given that Tønder would become Danish again. In February 1920, a referendum was held on nationality in the northern zone, to which Tønder belonged. The majority in the zone was overwhelmingly Danish, but in the town of Tønder, 75% voted German. Nevertheless, in June 1920, the citizens and the mayor of Tønder welcomed the Danish king and the Danish railwaymen - and not a saber rattled.

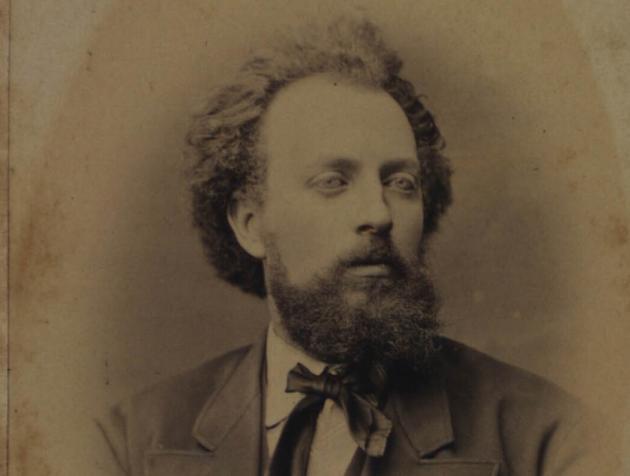

Derovre fra Grænsen, Holger Drachmann

Photo: H. Matsen

"It was as if the Dybbøl Mill did not want to go after the wind that was blowing here, and therefore had halted its speed until the right wind came."

In 1877, Holger Drachmann (1846-1908) published "Derovre fra Grænsen", a travelogue from the lost Southern Jutland, where he visited Dybbøl Mill and other historical places 13 years after the catastrophic defeat in 1864. The book was also a significant contribution to the debate. The Danish attitude to the new political situation was, what is lost outwards must be gained inwards

, but many Southern Jutlanders, as Holger Drachmann put it in his travelogue, still felt Danish-minded. This is most strongly expressed by a young South Jutlandic girl, whom Holger Drachmann met on his journey by a Danish soldier's grave in Bøffelkobbel: Do not forget us! she said as I said goodbye. Do not forget us!

The book became one of Holger Drachmann's most popular publications, and was also published in a Reunification edition in 1919.

Voter's association, school association and language association

Photo: Holger Damgaard

The cultural rearmament really took off in the 1880s, when Danish-minded people founded a number of associations with the aim of maintaining the Danish language and culture. The rearmament was a response to an increasing Germanization of Schleswig, which meant that Danish teaching and Danish schools were stopped by the German authorities. First came the "Association for the Preservation of the Danish Language in North Schleswig" in the autumn of 1880, then came the "North Schleswig Electoral Association" in the spring of 1888 and finally the "North Schleswig School Association" in 1892.

Photo: Ophav ukendt

The Voters' Association became the focal point of political development in Schleswig, and its leader H.P. Hanssen came to have great significance for the Reunification. In Aabenraa, the Language Association established Folkehjem with a library and community centre. It was from the balcony of Folkehjem that H.P. Hanssen proclaimed the Aabenraa resolution, which had great significance for the demarcation.

The school association often sent Danes on folk high school stays in Denmark, often at the folk high schools that the association had established just north of Kongeåen.