The library's secret collection

During the German occupation 1940-1945, Royal Danish Library secretly received a large part of the illegal press's printed matter. But one evening in 1944, the secret collection was revealed.

Photo: Ukendt ophav

During the war, the Danes received news from radio and newspapers, but both media outlets were under German censorship. However, this did not mean that the uncensored newspapers did not find their way to the Danes. In secret, the illegal press arose and grew huge during the occupation period. Illegal newspapers, magazines, pamphlets and leaflets were printed in the back of printing shops and in people's basements and attics. Secret networks were behind the distribution of the material and to get your hands on it, you needed to know someone who knew someone. If you were lucky, a specimen might also come flapping in the wind. But you could not keep it. Anyone who had read it had a duty to pass it on, so that the messages would reach all corners of Denmark.

Royal Danish Library was on the illegal newspapers' secret recipient list. In shady packages addressed to the Historian and with either a fake or no name as the sender, the library received countless illegal newspapers. Allegedly, there were only three employees who knew about this. Library director, Svend Dahl, head of the Danish collection, Richard Paulli, and the librarian, Albert Fabritius. The parcels were kept in a desk drawer behind lock and key, and when the drawer was full, the parcels were collected and transported to the archive, where they were placed under E: Discarded cases.

The interrogation

Photo: Ukendt ophav

Late one night in 1944, librarian Albert Fabritius and his pregnant wife were awakened by the Gestapo standing outside their door on the fourth floor. The Gestapo ordered the anxious couple to accompany them. In the dead of night, they were taken to the Gestapo headquarters, the Shell House, where Fabritius was interrogated. The Gestapo had intercepted illegal mail addressed to the Royal Danish Library. Fabritius answered the interrogation questions truthfully and confirmed that the library received illegal mail.

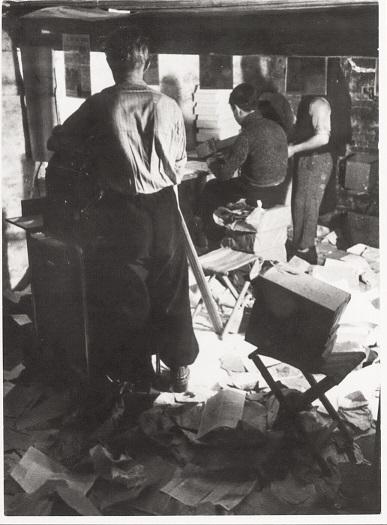

The Gestapo took Fabritius to Royal Danish Library and forced him to hand over the collection. At the time, there was no electric light in the library's storage facilities. And in the glow of the flashlights, the Gestapo forced Fabritius to hand over the ten packages of illegal mail that were closest to the door.

One of the Germans took a particular interest in a number of uniform packages in the room, but when Fabritius truthfully explained that they contained tax lists from the Municipality of Copenhagen, which were supposed to lie untouched for 100 years, the man was seized with awe and gave up the further search.

The Germans never discovered that the ten packages were just a fraction of the secret collection's contents.

After several interrogations and a short visit to Vestre Fængsel's cell 352, Fabritius was released. He was forced to promise that he would stop collecting the illegal newspapers - but it did not work out that way. Fabritius and Svend Dahl continued to hide the illegal mail, but instead of storing it in the desk drawer and in the archive's E section, they instead stuffed the mail behind the shelves, where the occupying power would be unlikely to find it in a new raid.

But a new raid never took place, because six months later the message of liberation was heard.

Part of the storytelling

Shortly after Denmark's liberation, the Danes began to talk about who we were and what actually happened in Denmark during the occupation. Here, the illegal newspapers, which were Denmark's free voice during the occupation, played a significant role as documentation. As early as the summer of 1945, the secret collection was exhibited in the exhibition Denmark under occupation.

The collection of the then illegal printed matter is still part of Royal Danish Library's collections. You can find them by searching our library system.