Beautified pictures

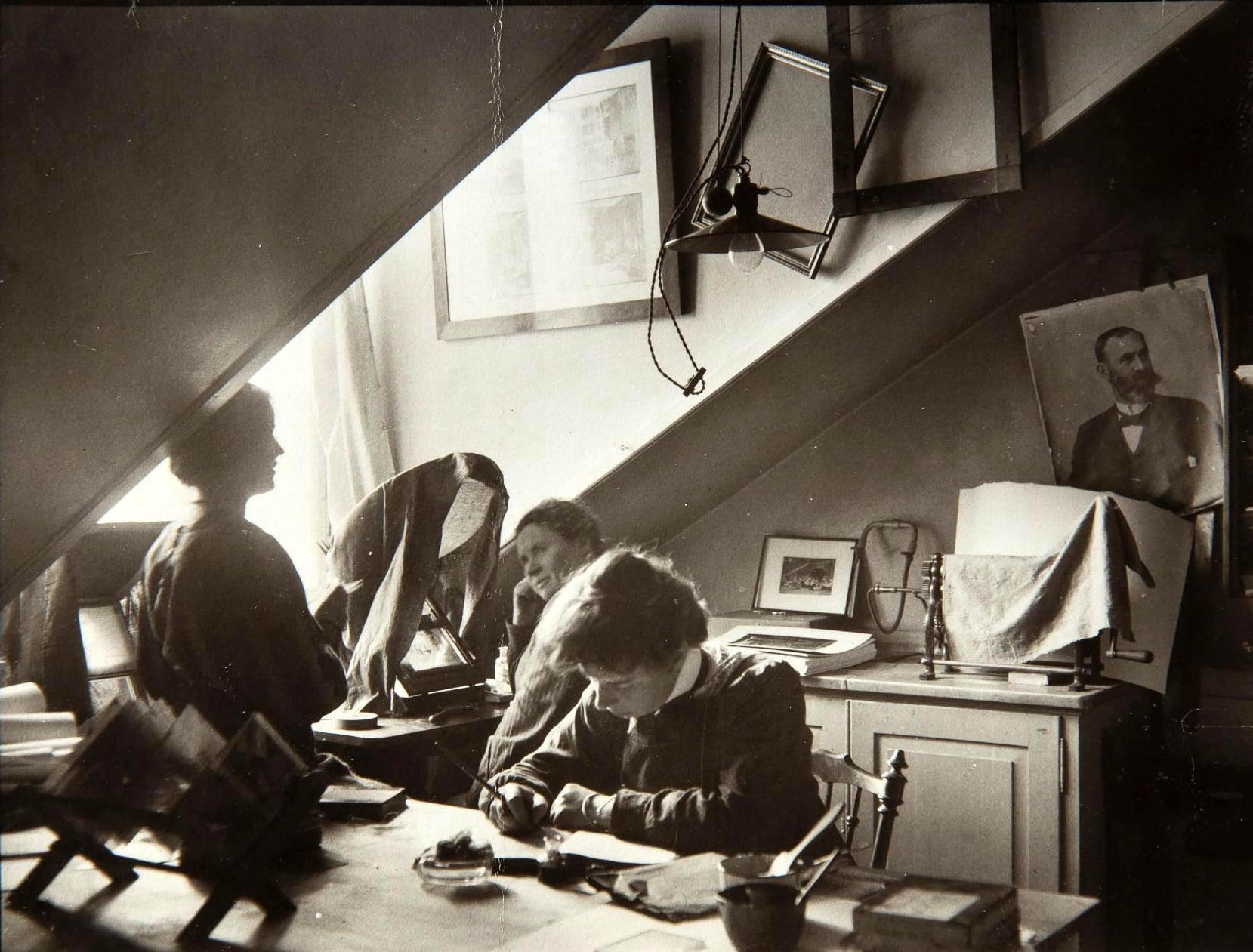

The photographers had skilled retouchers on staff. They scratched out the negatives and drew on the positives.

It was laborious to photograph around the year 1900. The camera was made of wood and large and heavy. The negatives were first glass, then acetate, and they required a lot of light. That is why the studios were typically located in the attic under the roof. Once the photographer had exposed, the negative had to be developed in liquids in a darkroom. Sometimes there were areas on the negative that were a little too light or dark, or there were little scratches or the like. There were also customers who required a bit of processing to look better.

Photo: Peter Elfelt

That is why there were women who worked with retouching. The word comes from French and means "to touch again", and what was touched again was negative or positive. The negative sat in a so-called retouch box, on a glass plate with a light behind it, so the retoucher could see what she was doing. She mixed up turpentine with some graphite and used it to even out areas that needed to be lighter. Or she scratched a little in the emulsion if something was to be darker. A skilled retoucher could remove wrinkles, apple cheeks and give a slightly narrower waist.

Positives were retouched with pencil or ink. For example, it was common practice to make a black dot in the pupil, but it had to be done precisely, otherwise it would look as if the model was squinting.

Laurberg and Gad's negatives are generally of a very high quality. That is to say, a lot of work was spent on lighting before and during the recording, and not a lot of work was necessary when developing the negatives.

Laurberg and Gad in Digital collections

Royal Danish Library has a collection of 4,400 negatives by Julie Laurberg and Franziska Gad. It has been digitised and made available in Digital Collections. Here you can also find many paper images, both portraits and architectural images, from Laurberg and Gad's studio.