Jacob Chr. Bie - an annoying guy

Join us on a trip from Hvidovre Church to Serampore in India. Follow us into Rasphuset and learn about one of Denmark's first keyboard warriors, who used a pen and printing press instead of Facebook.

Do you know someone who never knows when to shut up? Someone who is a little too clever for his own good - and not afraid to talk about it? This is the story of Jacob Christian Bie.

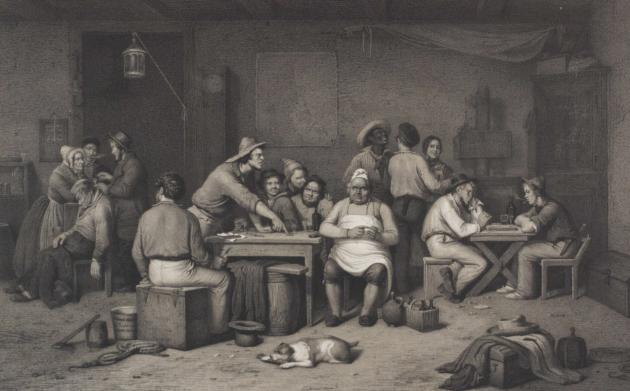

Hvidovre Church is full. It is July 1769 and there is still censorship in Denmark. The rumours are running amok. Those who did not leave the brandy and card game when the bells rang for church service slink into church and sneak into the back pews. Standing tall at the pulpit, Jacob Christian Bie has taken over the Sunday sermon. According to the village rumours, it is definitely not boring.

Jacob Christian Bie is a well-known figure in Copenhagen. He makes a living from writing. The money is small, but Bie is quite adept at cranking out a quick party song or poem. Words are his way of life but they also become his downfall. He finds it difficult to rein in his humorous wit, some even call him downright vicious, and stepping on the wrong toes in 18th-century Copenhagen can be dangerous.

In Hvidovre, Bie continues to preach the Song of Songs. The Bible scholar knows that the hymn can be read a little more suggestively than other texts in the Bible. Bie knows that too. He knows his Bible and he recites with a loud voice and accompanying gestures: In my bed at Night I sought the one Whom my soul loved.

Hvidovre's farmers widen their eyes. The sources disagree a bit on whether they are hooting and laughing, but something may indicate that.

On 14 September, 1770, Christian VII introduces freedom of the press in Denmark. The censorship is over. It is no longer necessary to submit your text to the high and mighty at the University of Copenhagen to be allowed to print. In fact, you do not even have to add your own name to what you print any longer. Writers can appear completely anonymously.

Photo: Georg Fahrenholtz

Back in 1769, Jacob Christian Bie completes his sermon. Evil wagging tongues later say that he ends his remarkable sermon by praying for a number of specific women from Copenhagen, all of them notorious - even as far away as Hvidovre - for trading in their charms

. Whether it really is the content of the closing prayer, we do not entirely know, but in any case, Bie's behaviour creates a scandal.

Immediately after the introduction of freedom of the press, a publication is sold in the streets of Copenhagen. It is signed Philopatreias. In the writing, the writer laments the costly food prices, the lengthy lawsuits where a poor man often has to suffer injustice

and not least the priests' excessively high wages. It is, of course, Jacob Christian Bie who hides behind the pseudonym. He cannot resist the temptation to immediately skewer some of his favourite aversions, the justice system and the priests.

Photo: C. A Schleisner

The writing arouses great attention. Jacob Christian Bie jabs at the leaders of society. It is the talk of the town in both the pubs and at home in people's living rooms. The indignation is great in some; others are more or less openly gleeful that the government gets lambasted. It will be the beginning of a whole debate, spanning 62 writings by several different writers. Bie also continues to publish pamphlets into 1771. But the incident in Hvidovre Church catches up with Bie. He is sentenced to six years in prison in Rasphuset for his outspoken sermon. He himself claims that the sermon was completely peaceful and that the peasants in Hvidovre behaved reverently throughout. The verdict is harsh - even seen with today's eyes. Jacob Christian Bie, however, is not that easy to knock down.

From Rasphuset, Bie continues to write, often in the form of poetic lamentations. Maybe it is this stream of writings that makes the authorities reconsider? In any case, Bie is supposed to be released by royal order on 13 October, 1775, but senior officials still hold a grudge against Bie and they interfere in the release. Bie had to wait until 1777 for his release, but his struggle did not end there.

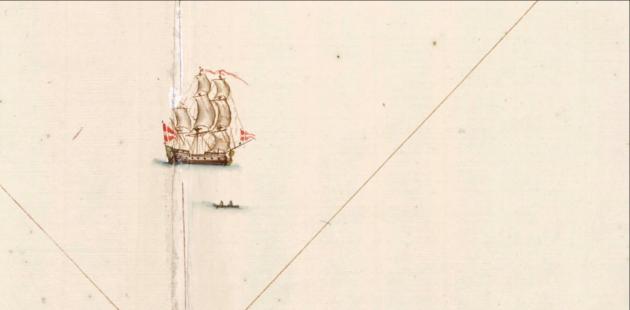

Guards slam cold iron chains around Jacob Christian Bie's wrists. They lead him out of prison, through the streets of Copenhagen and row him out to a ship anchoring in the harbour. The crew has orders not to let him roam free while in port, so they chain him to the hold. The next morning the ship sets course for the Danish East Indies.

Photo: Ophav ukendt

In Serampore, or Frederiksnagore, as the colony is called in Danish, Ole Bie is waiting. He has promised to take care of his smart-mouthed brother. It is his intercession that has brought Jacob Christian Bie out of Rasphuset. But Ole Bie will to some extent regret his loyalty to his brother. In 1792 he writes, clearly frustrated, that everyone who gets into trouble

turns to Jacob Christian Bie to be saved by his ingenious advice and legal tricks

. Captain Jacob Krefting, who later succeeds Ole Bie as chief secretary of the colony, says bluntly: So long as a certain Jacob Chr. Bee is not expelled from the colony, it is flat out impossible to get the place in order. This man corrupts everyone who comes here, puts like-minded people together, gives advice that is revolting [and] seduces young people away from moral virtues to moral vices.

Jacob Christian Bie was, however, never expelled from the colony. He lived in India until his death.

Freedom of the press writings

Dive into the many writings from the time censorship was abolished.