EC 2024: South Slavic ghosts

A historical look at the upcoming European Championship finals in soccer. Once Yugoslavia was one country, today it is seven. The Danish men's national team will meet two of them in the group stage.

When Sre ć ko Katanec left the old Copenhagen Sports Park on a Wednesday evening in November 1990 and cast one last glance towards the shining floodlights in the dark autumn evening, he probably had no idea that it would be his last international match for the country he had grown up with up as part of and which had shaped his 27-year-old life so far.

The Danish men's national team has qualified for the European Championship 2024. In the opening group stage, the opponents are Slovenia, England and Serbia. This has given us reason to look in the archives. England and English soccer carries its own long history. Serbia's and Slovenia's are far shorter, but what exactly happened to Yugoslavia, the nation that once housed both Serbia and Slovenia in a common federation?

Facts: Yugoslavia

The name Yugoslavia actually existed until 2003 – in the end, however, only as the designation for the federation between Serbia and Montenegro. But the actual socialist federation of Yugoslavia dissolved in 1992 after Croatia and later Bosnia/Herzegovina declared themselves independent nations.

Photo: Holger Damgaard

Let us start back in Copenhagen Sports Park, November 1990. Slovenian-born Katanec had played a solid game in defensive midfield for Yugoslavia. The Yugoslavs had just won 2-0 and they were well on their way to qualifying for European Championship 1992 in Sweden. The match in Copenhagen was a key match.

Club-wise, he was heading into his best season to date. He played on a daily basis for the Series A top team Sampdoria and half a year later was to celebrate the Italian championship, Lo Scudetto, with the Genoa club.

But when Katanec could lift the trophy, Slovenia had voted itself out of the Yugoslav Federation of States. That same summer, independence came after a short war. It was the first step in the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the beginning of the cruel civil war that came to characterise Europe in the 1990s.

The extent to which Katanec was aware that it was also the last game in the old Copenhagen Sports Park is unclear. But when the stadium lights were turned off over the old stadium on Østerbro, two years had to pass before it was resurrected as a more modern Parken.

Although the floodlights were turned off for the last time, the focus was still on the Danish national team. The newly appointed coach Richard Møller Nielsen and the team's efforts were the subject of fierce debate. There was talk of a lack of joy in playing and both Laudrup brothers chose to not continue on with the national team after the Yugoslavia game.

A good year and a half after the – for us Danes – sad game in the Sports Park, the national team stood as European champions at Nya Ullevi in Gothenburg. An EC we never managed to qualify for, even though the return match in Belgrade, May 1991, actually ended 2-1 in Denmark's favour. Yugoslavia was excluded due to the civil war a few weeks later and Denmark joined instead. From there, the summer of 1992 has become a well-known story.

Incidentally, the match in Belgrade was to be the last between the two nations. The statistics tell of nine international matches in total. In addition, there were a number of matches between Yugoslav clubs and select Danish teams. Behind a few of them are hidden interesting stories.

Belgrade 1950

It began where it also ended. In the capital of present-day Serbia. Belgrade. The Danes got a shock at this first meeting between the countries. They lost 5-1 and the bulletins reported that it could easily have been worse figures.

"The players were almost paralysed that the Yugoslavs really played so well. After all, they hadn't expected that.”

The Danish goalkeeper, Eigil Nielsen from KB (Kjøbenhavns Boldklub), started the match unluckily by missing a long shot in the goal. But ended up being praised, not just by BT's dispatchers, but apparently also by the local spectators. Estimated 60,000 at the Yugoslav People's Army Stadium.

... he got a lot of applause from the expert Yugoslav audience, so despite the one big minus, he should definitely be praised. He handled many hopeless situations and definitely limited our defeat.

The all-round sportsman, soccer player and journalist, Knud Lundberg, stated in Information on 29 May 1950: Technique, sheer takedowns, dribbling, ball feel and body balance were the most behind us. It wasn't much that these Yugoslavs couldn't do with a ball.

In the newspaper Social-Demokraten, the defeat caused reflection a few days after the match in Belgrade. It was amateurs against professionals and the debate as to whether the Danish national team should play against semi- or fully professional nations in the future was aired. However, this was pointedly rejected by DBU. Officially, the Yugoslavs were amateurs, but the players had jobs under state auspices. Typically the police or the army, where soccer could be prioritised. The communist regime knew how to reward its best sportsmen.

Club team on charm offensive

Just over 10 days passed before the next Danish meeting with Yugoslav soccer. This time, the Copenhagen soccer association, Stævnet, invited two matches in Idrætsparken against the club team Metalac. Presented as fifth best club in Yugoslavia. Today, they are known under the name OFK Beograd and the team tempts an existence in the second best Serbian league.

There were two defeats for the selected Copenhagen teams with different starting line-ups and changing quality. 1-7 and 0-1. The two matches were played three days apart, and for the second match, Stævnet mustered seven of the national team players who had played in Belgrade.

What was Stævnet?

Stævnet or The International Soccer Convention. A Copenhagen soccer association formed in 1904 by KB and B93. Later came AB, B1903 and Frem. Even later, more Copenhagen clubs. The convention organised exhibition matches where they fielded joint teams and met international opponents. Swedish and English teams in particular were frequent guests at Idrætsparken. The competition existed until 1979, when they met Manchester United in a final match.

One of the others was the aforementioned Knud Lundberg from AB, who - this time - in his role as a striker was able to speak to Berlingske Tidende on 8 June 1950.

How I regret it! It's my first home defeat - i.e. in the Sports Park - since we lost to the Netherlands a year ago. It would have been fun to make it through the entire season without losing.

And as Berlingske noted. Lundberg had good reasons.

Because he had played so well and given his fellow forwards so many good chances in the 1st half that he should not have had to leave the pitch.

For Metalac, it was the beginning of a summer tour where, after a trip to Sweden, they played exhibition matches in Aarhus, Randers, Aalborg and Næstved. A summer trip on behalf of the Yugoslav state. It was a point of interest to stand well with Western Europe and establishing friendships. Although the country was officially a socialist republic with a communist one-party government, Yugoslavia never became an integral part of the rest of the communist Eastern Bloc. The long-time leader and freedom hero Josip Tito had a strained relationship with the Soviet Union, and not least Josef Stalin in the years after World War II, and kept the country on a neutral foreign course. Yugoslavia was supposed to be different. Midway between East and West – outside the Iron Curtain.

However, not everything went completely smoothly on the charm tour around Denmark. On 23 June 1950, Randers Amtsavis reported on Southern temperament

and wrote:

A transition reminded the stadium more of a Spanish fencing arena than a soccer field, and most people left the stadium with a somewhat mixed impression of Marshal Tito's favourites.

It was a missed penalty kick, which the referee judged should be re-kicked, that triggered the sour atmosphere at Randers Stadium. What remained, however, was the impression that the Yugoslav players had once again impressed with their technical skill and playing skills. To underline the soccer qualities, three Olympic silver medals could also be added. At the games in London 1948, in Helsinki 1952, and Melbourne 1956, the Yugoslavs reached the final. But lost.

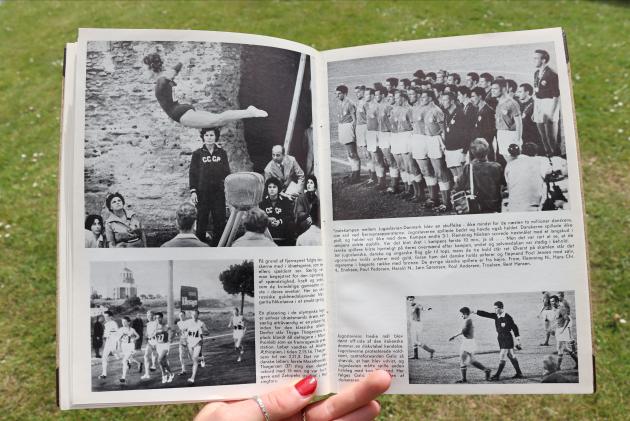

Rome 1960

The Olympic soccer tournament was still relatively large at the time. However, the major European and South American countries could not use professional players. It was against the Olympic Code. This meant that the tournament was mostly dominated by Eastern European state amateurs. Opposite the WC.

The EC as we know it was played for the very first time a few months before the Olympic final. Incidentally, between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in Paris, and with yet another Yugoslav final defeat as a result.

The final was played on 10 September 1960 at the Flaminio Stadium in Rome. In Danish soccer history, the semi-final victory four days earlier at 2-0 over Hungary stands far stronger than the final itself. With good reason. The Danes played a great match against Hungary and it was in the semi-final that AGF goalkeeper Henry From placed his chewing gum on one of the goalposts before the opponent had to take a penalty kick. It distracted the Hungarian kicker so much that he missed.

... 5,000 Danish spectators threw hats, programmes and bags in the air in true jubilation

, reads the description in the Olympic Yearbook. The great Danish hero was Frederikshavn's Harald Nielsen. Dubbed Gold Harald by the press. Nielsen insisted all along that Denmark would win the gold. Both before and during the tournament. In the final, he was convinced that Denmark would win 3-0.

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

It did not work out that way. Yugoslavia won 3-1. Quite convincingly. It was 2-0 after 11 minutes of play and 3-0 was on the way shortly before the break. But the match's Italian referee believed, questionably according to many observers, that the Serbian striker Milan Galić had run offside and nullified the goal. Galić became enraged and allegedly shouted the Serbo-Croatian word for "arsehole" at him. Unfortunately, the referee was familiar with the jargon of the neighbouring country and promptly expelled the Yugoslav.

The expulsion of Galić in turn ensured that Harald Nielsen ended up as the tournament's top scorer with his 6 goals. At least according to a number of different Danish newspapers, and it was later repeated in other Danish sources. In the international media, however, Galić is the top scorer with 7 goals.

Although the Yugoslavs played a man down throughout the 2nd half, the victory was never in jeopardy. It was 3-0 in the middle of the second half, while AB's Flemming Nielsen only kicked in the last seconds of the game.

The Danish soccer players burned out a game too early, but otherwise exceeded all expectations, and therefore they deserve the great tribute

, stated Jyllandsposten the day after the final.

Gold Harald was soon to continue as a professional in Italian Bologna, which cut him off from the national team for the rest of his career. DBU did not accept professional players in the national team until 1971. The Danish view of professional soccer in 1960 was revealed by Jyllandsposten's comments after the final match in Rome.

When you look further down here, you see the type of "monkey soccer" these semi-professional meatballs serves and the deluge of unregulated games they allow, yes, then the award goes to Danish soccer again.

Silver medals for the true amateurs. The silver team. While the other nations dished out... A form of game that can only bring the noble game of soccer into disrepute, and in fact only makes this kind of soccer significantly more violent and dangerous to life and limb than the much-discussed sport of boxing.

The writer emphasises, however, that it – almost! - did not apply to the Yugoslavs' game in the final.

Lyon 1984

Professionals versus amateurs was no longer a theme in Danish soccer when the men's national team met Yugoslavia for the seventh time. Times had changed, the best players, regardless of payment and club address, now played in the national team. And the best Danish players were becoming a really strong unit under the leadership of German coach Sepp Piontek.

Photo: Nordisk Pressefoto

In the previous 6 international matches between them, the Yugoslavs had won all six. A statistic that Piontek did not bother to take an interest in before the match at Stade Gerland in Lyon. It was European Championship 1984 and the first major final round for the Danish national team in decades - well, ever. If you disregarded a few Olympic tournaments.

The fact that Denmark has lost to Yugoslavia six times out of six belongs in the statistics and not in the team's reality,

Piontek told Berlingske Tidende in the prelude. The midfielder, Søren Lerby, then with an address in Bayern Munich, added.

I don't think it will be a battle of morals. Of course, it is always good to get ahead, because then you can pull back a little and play waiting. But the early goal is not decisive. As long as we win, it doesn't matter if we only scored in the 89th minute.

There was a lot of talk about Yugoslav morale after their first match. A 2-0 defeat to Belgium. They had shown themselves fragile in adversity and were looking for past glory. A new national team under construction. One of the young players was a 20-year-old defensive player with Slovenian ancestry, already mentioned Sre ć ko Katanec. He had been re-elected against Denmark, but the coach replaced four others for the match. One of them was the goalkeeper.

Denmark also came to the match with a defeat. 0-1 to the host nation. Make or break. The scene was set on Saturday evening, 16 June in Lyon. It was a total loss for the Yugoslavs. Already after 8 minutes of play, the new goalkeeper, Tomislav Ivković , fumbled a kick from the backline in his own goal. Goalscorer Frank Arnesen disagreed.

I could see that the Yugoslavian full-back was standing still as I approached, so I just poked the ball right around him with my toe and moved inside and past him in the box. He was completely sent off and I reached the ball again all the way down by the back line out on the right side of the box. And then I shot on target.

, reads Arnesen's own description. Quoted from the book "My biggest fight", 2019.

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

Just eight minutes later, Ivković looked uncertain again when he had to parry a ball coming towards the small box. He was too late and Michael Laudrup tipped the ball over the helpless keeper. Klaus Berggreen was subsequently able to slide it into the goal. 2-0. Make or break. A make for Denmark. In the 2nd half, it was a pure display. Arnesen used a penalty kick to make it 3-0, while Preben Elkjær and Espanyol player John Lauridsen made it 4 and 5-0. It was estimated that around 16-20,000 Danes were in place at Stade Gerland. That was before people started talking about roligans, non-violent soccer fans.

Saturday was the day when Danish soccer really found the grimace that suited us best. It was no coincidence that we qualified for the EC final round. It was no coincidence that we played the French favourites in the opening match. Just ask the Yugoslavs

, BT cheered.

No one really bothered to ask the Yugoslavs. But for the first time in soccer history, Denmark had defeated the otherwise impressive Yugoslavs. Even on the biggest stage, a European championship, and the seed was laid for the national team that in those years - in the mid-1980s - was to become one of Europe's best.

For the Danish team, the victory extended to a later semi-final against Spain. A regrettable defeat on penalty kicks and Elkjær's torn trousers.

For Yugoslavia, it was an exit from France and a longer deroute into national team darkness. They only participated in the major final rounds again at the 1990 World Cup – the last swan song before the cruel shadows of civil war dissolved the country.

The sources

We have used several newspaper articles from Danish daily newspapers, match programmes and pictures in Royal Danish Library's collections as sources for this story. In addition, there are a number of books:

Photo: Det Kgl. Bibliotek

- The Olympic Yearbook, KBH 1960, edited by Rickard A. Nielsen

- Harald og Flemming fortæller, KBH 1961, by Harald Nielsen and Flemming Nielsen

- Guld-Harald, KBH, Gyldendal 2009, by Joakim Jakobsen

- Min største kamp, KBH, Storyhouse, 2019, Danish soccer stars talk about the biggest soccer match of their lives.

Ghosts

Sre ć ko Katanec was 20 years old when he ran into Stade Gerland for the match against Denmark. He probably does not remember that night in Lyon fondly. He had been part of a team in disarray and conceded Yugoslavia's biggest defeat in 33 years. He was shown a yellow card after a rough tackle on Berggreen in the first half, and had to be replaced early in the second.

14 years later, a Slovenian national team ran on the pitch at an EC for the first time. On the bench at the European Championship 2000 in Holland/Belgium sat Katenec, who, after club triumphs in Germany and Italy, had put his boots on the shelf, but not soccer. He was now Slovenian national coach.

The irony of fate made it so that Slovenia ended up in the same initial group as a new Yugoslavia. A Yugoslavia which at that time was really only Serbia and Montenegro. Back then, the match ended 3-3.

In Euro 2024, Serbia and Slovenia meet. With all the Yugoslav ghosts of the past hanging over the green - and with Denmark and England as fellow combatants in the opening group.

In the library's collections, you can find Yugoslav ghosts, former English great teams and Danish Olympic winners. For example, look for soccer pictures or newspaper articles.