Strike a pose

We may have always tried to encapture people's likenesses in images, but it is only with photography that everyone gets the opportunity to have their portraits done.

Today we can take a portrait with our mobile phones in an instant. When photography was first invented, the process was more cumbersome, but still a revolution. Before, only the rich could afford to have a picture painted of them, but now many more could have their portrait taken.

At first, the technique seemed like magic because the process was mechanical and the pictures were such good likenesses.

Very soon, famous and unknown people alike began to pose before the photographer’s lens. Individual photographers developed their own signature style and way of bringing out the personality of their sitters. Today, photographers often reinvigorate the portrait genre with new approaches to composition or by revealing something unexpected about the sitter.

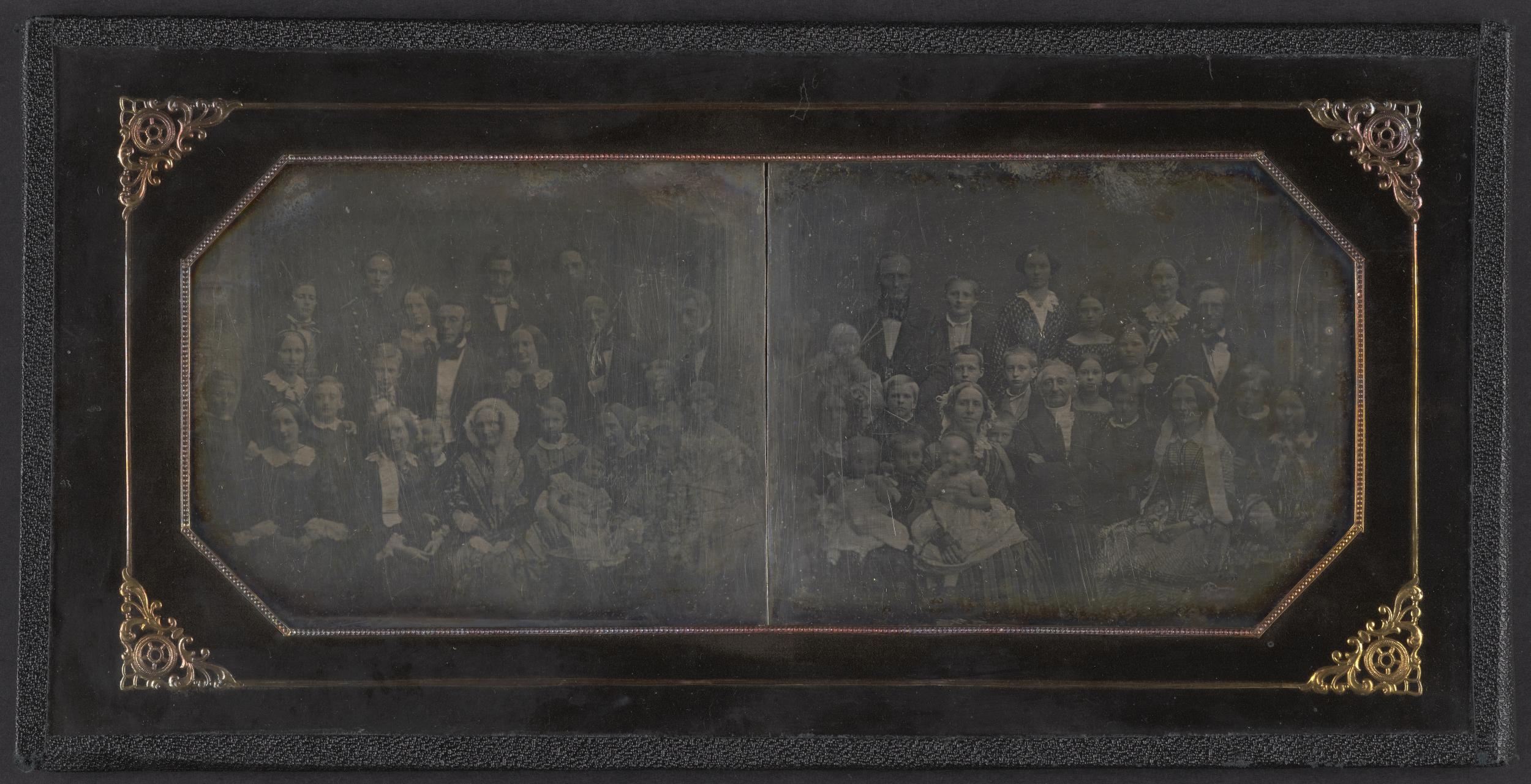

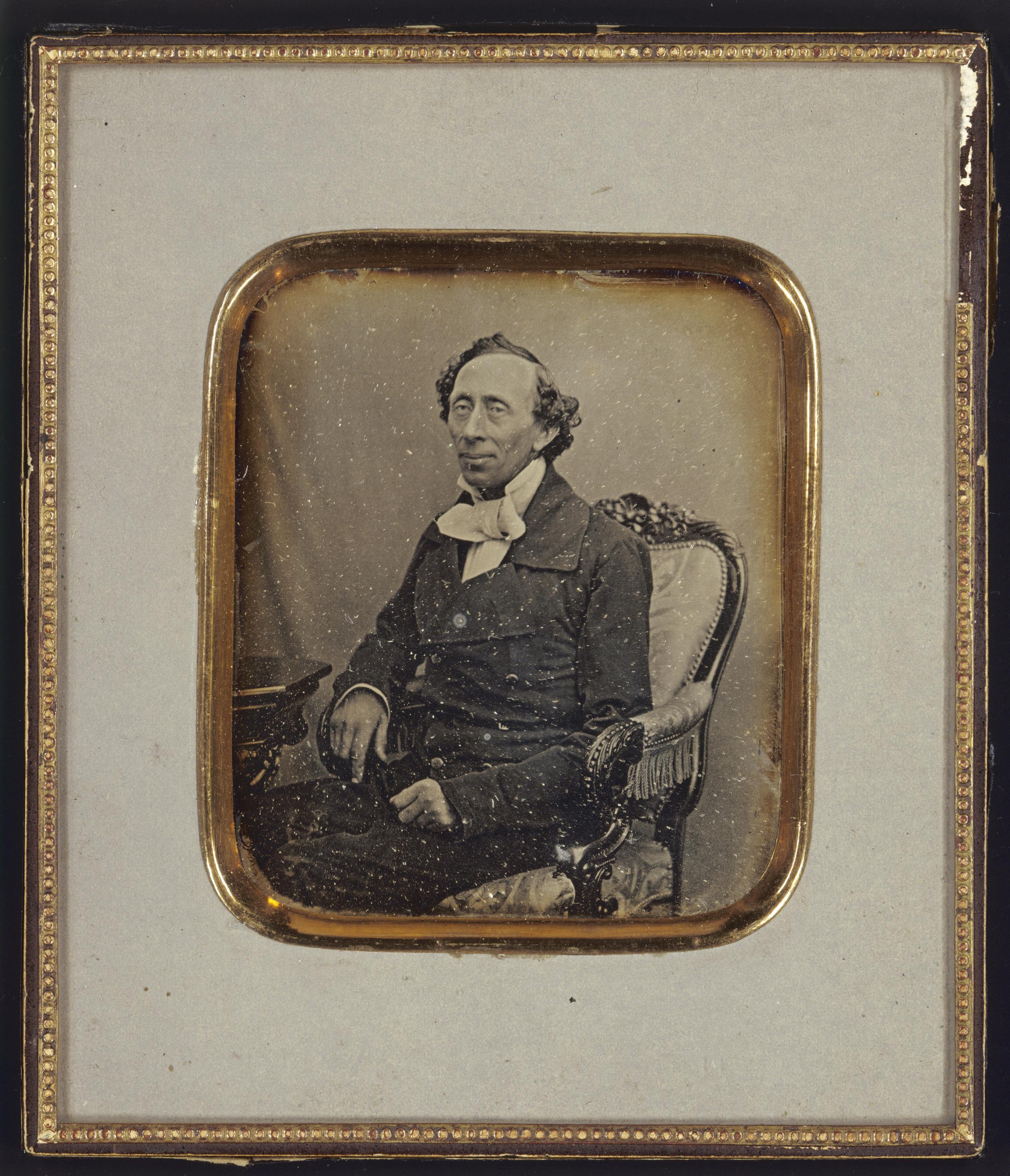

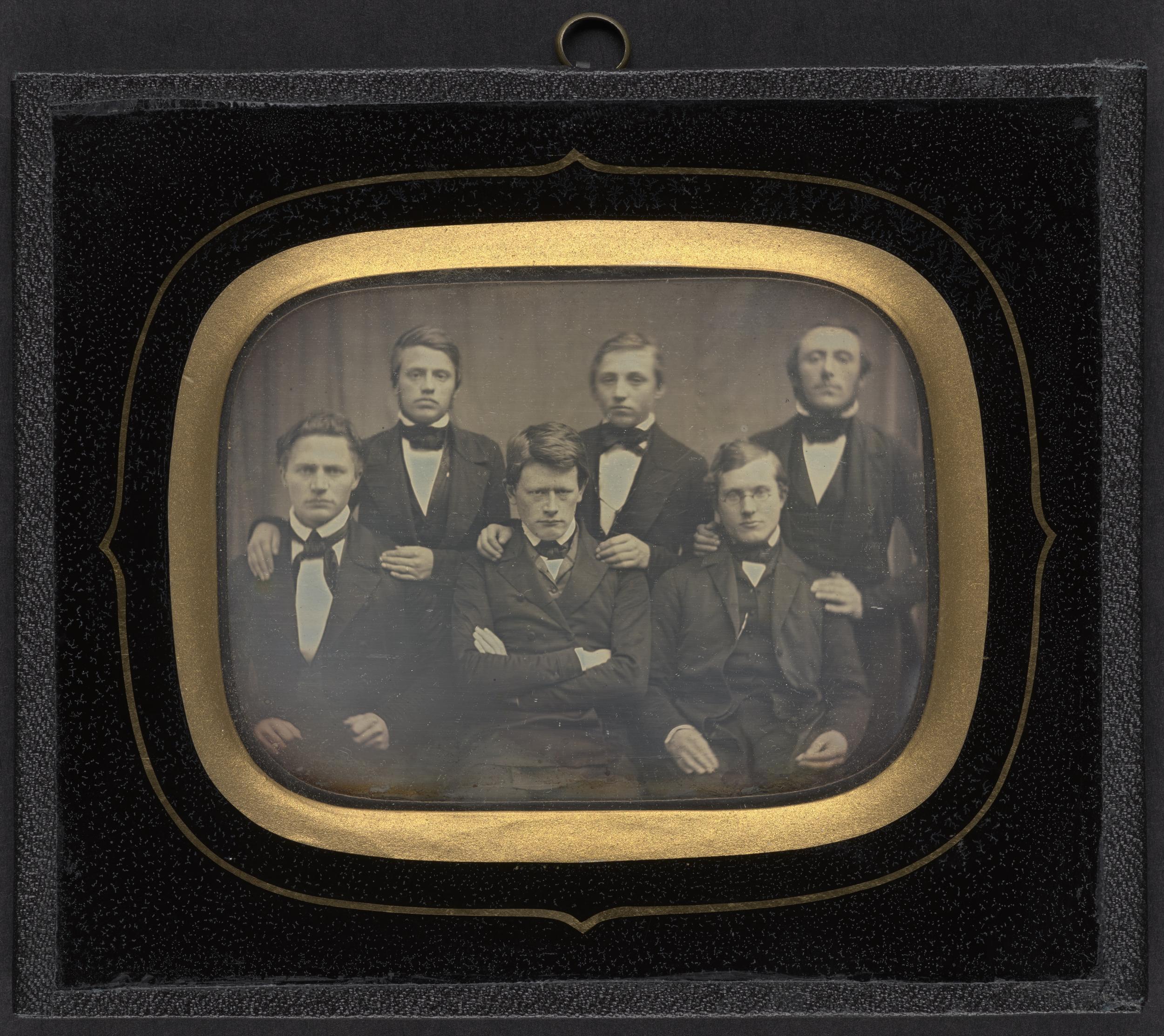

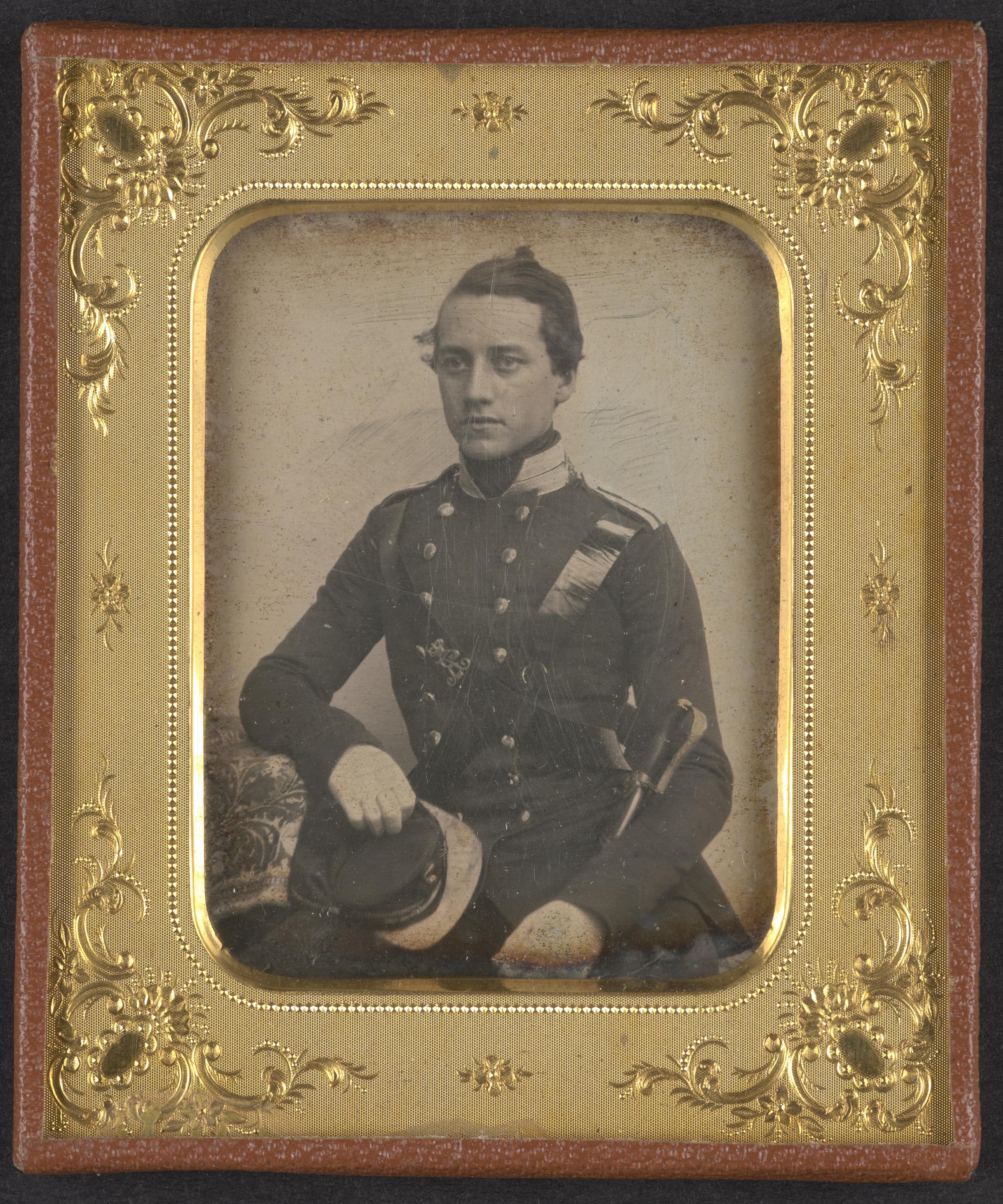

The first portraits

In 1839, the French artist Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre succeeded in capturing a picture on a plate treated with silver iodide. This first photographic technique was named a ‘daguerreotype’ after the inventor. The technique gained ground in Denmark the following year, and soon many affluent people began to visit the temporarily set-up studios to be portrayed in this new and somewhat mysterious medium. At first, sitters had to remain still for a long time in front of the camera, giving the portraits a somewhat sombre look. Some, however, had already learned how to smile at the camera.

Royal Danish Library began collecting daguerreotypes and other early photographs such as ambrotypes in the twentieth century and now houses the largest collection in the Nordic countries of pictures from this early stage of the history of photography.

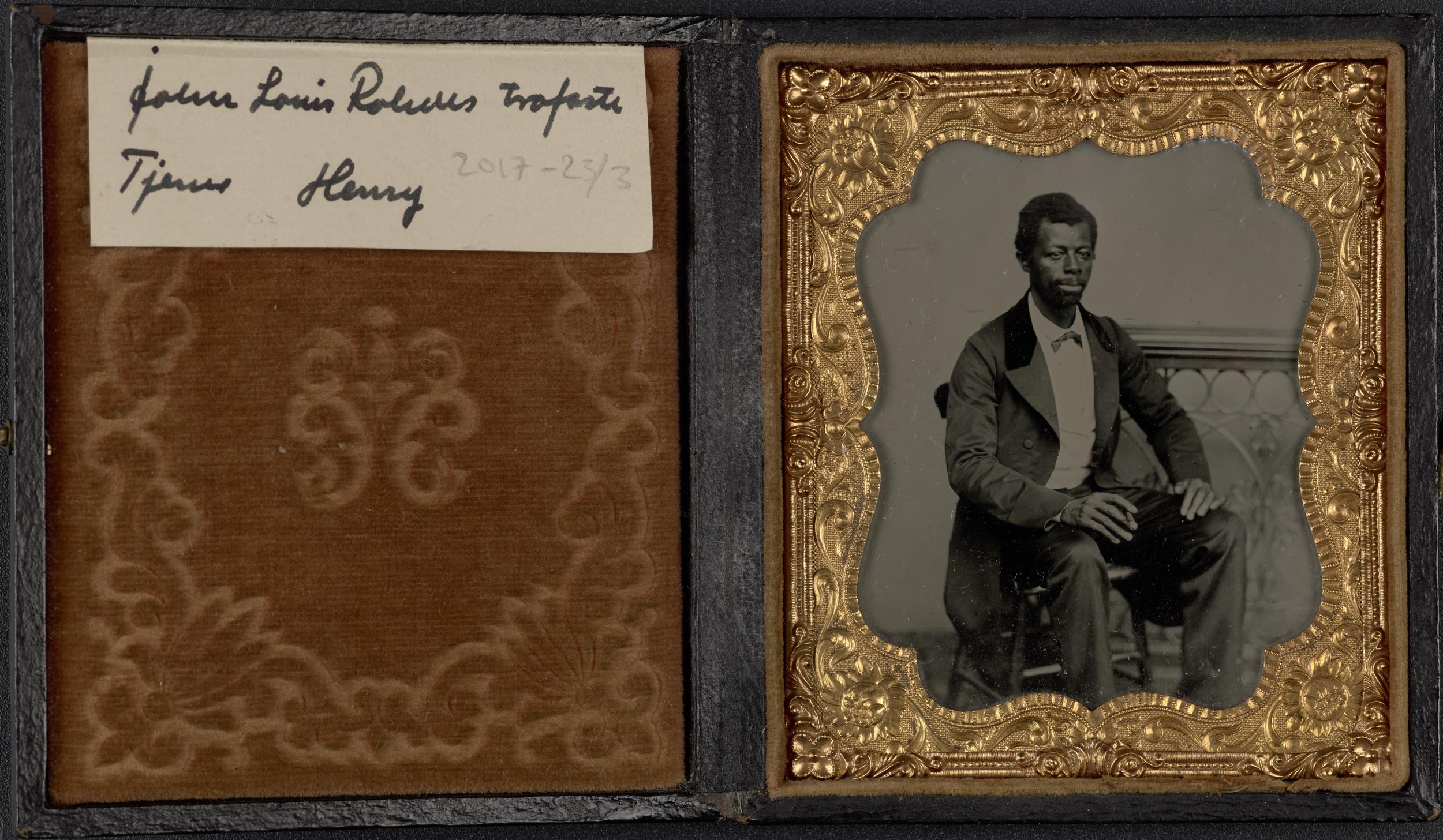

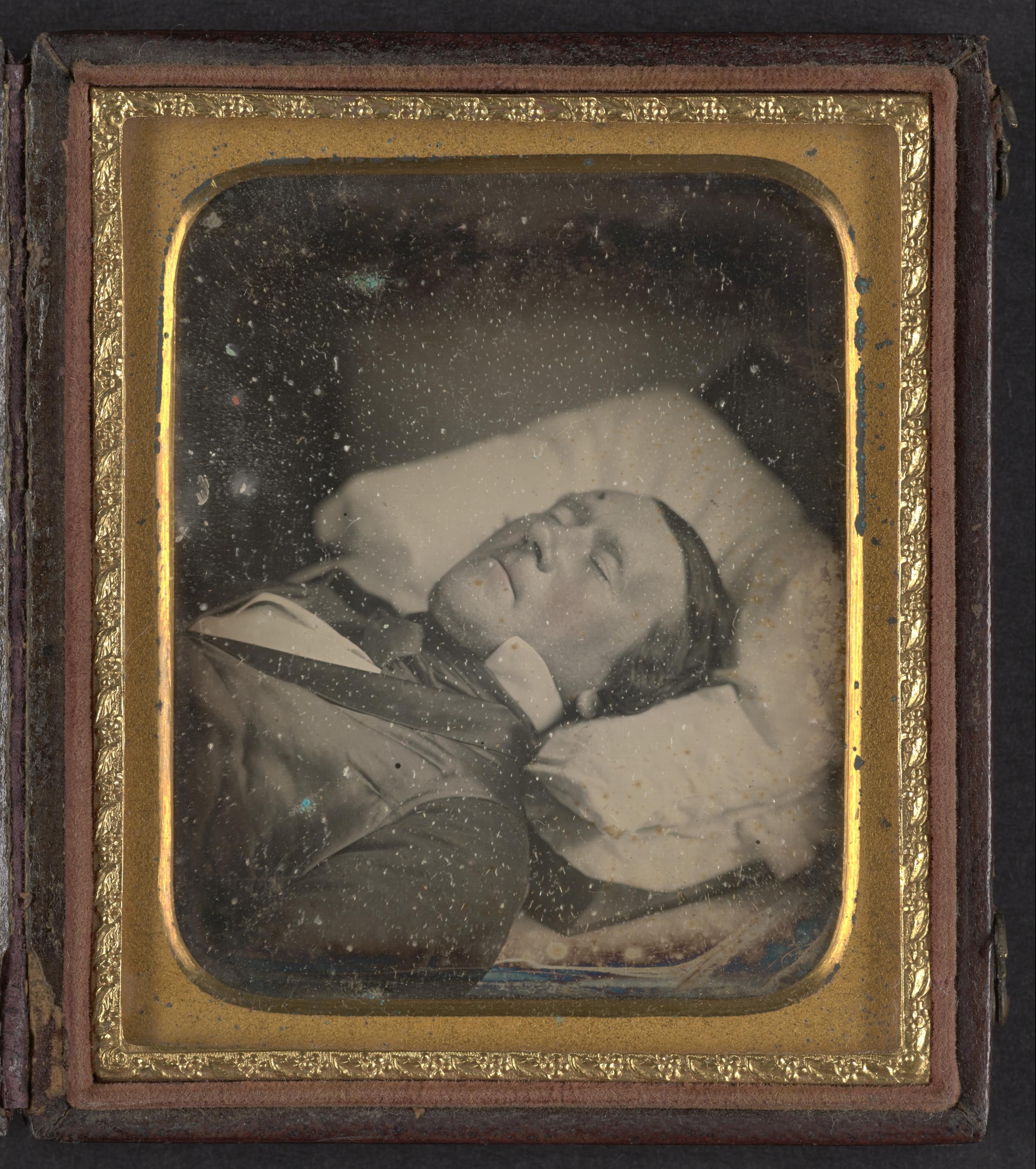

Depicting the dead

Photographs of deceased relatives were highly valued in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Being such good likenesses, they created a special sense of connection to the portrayed after their death. Older people were photographed to have something to remember them by, and looking at such pictures after their death could almost evoke the feeling that they had returned from the dead. Having portraits taken of dead people – so-called post-mortem photography – also became commonplace.

Today, only very few people would invite a photographer to take pictures of the deceased, but many take a very last picture themselves to say goodbye.

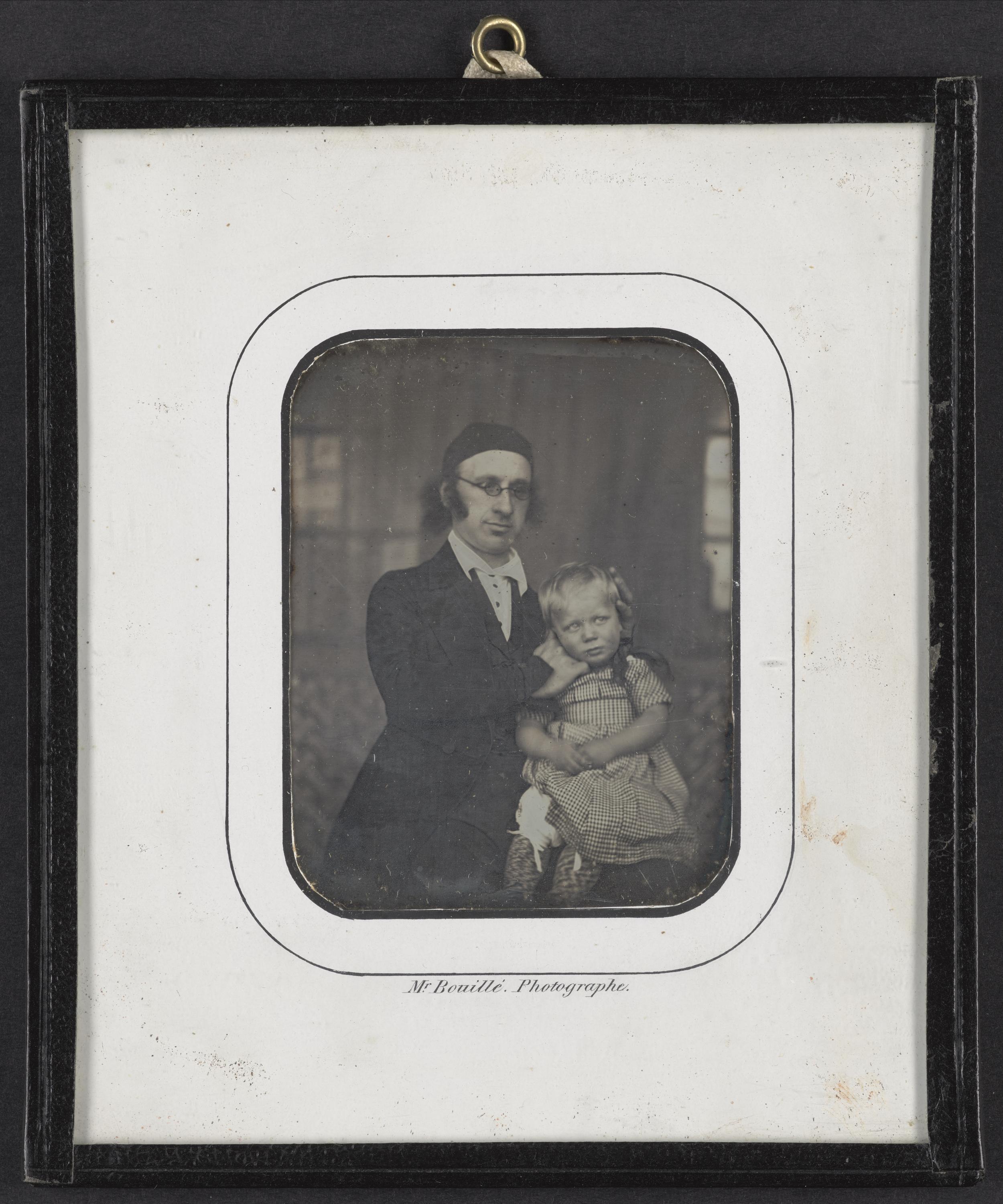

Photo jewellery

Today, many people carry pictures of their partners and children on their mobile phones. The practice of carrying a photograph with you dates all the way back to the birth of the medium, when daguerreotypes replaced miniature paintings in the brooches, cases and pendants. Many were fascinated by how closely the picture represented reality – by how light itself had left its imprint,

creating photographs. It was called ‘Nature’s own image’. When you carried such images close to you, the sense of connection to the person portrayed became extra strong.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Princess Marie of Orléans

In the 1860s, the negative/positive process replaced the daguerreotype technique. Photographic studios sprang up in cities and towns, and a wide selection of people now put on their best clothes and went to the photographer. So-called carte de visite photographs were handed out freely to friends and acquaintances. Portraits of famous people were also collected.

One of the more colourful characters was princess Marie of Orléans, who married a Danish prince. She not only had herself immortalised in fine dresses and jewellery, but also in the company of her dogs or wearing the firefighting uniform she actually used as an active member of the Copenhagen fire department.

Familiar faces

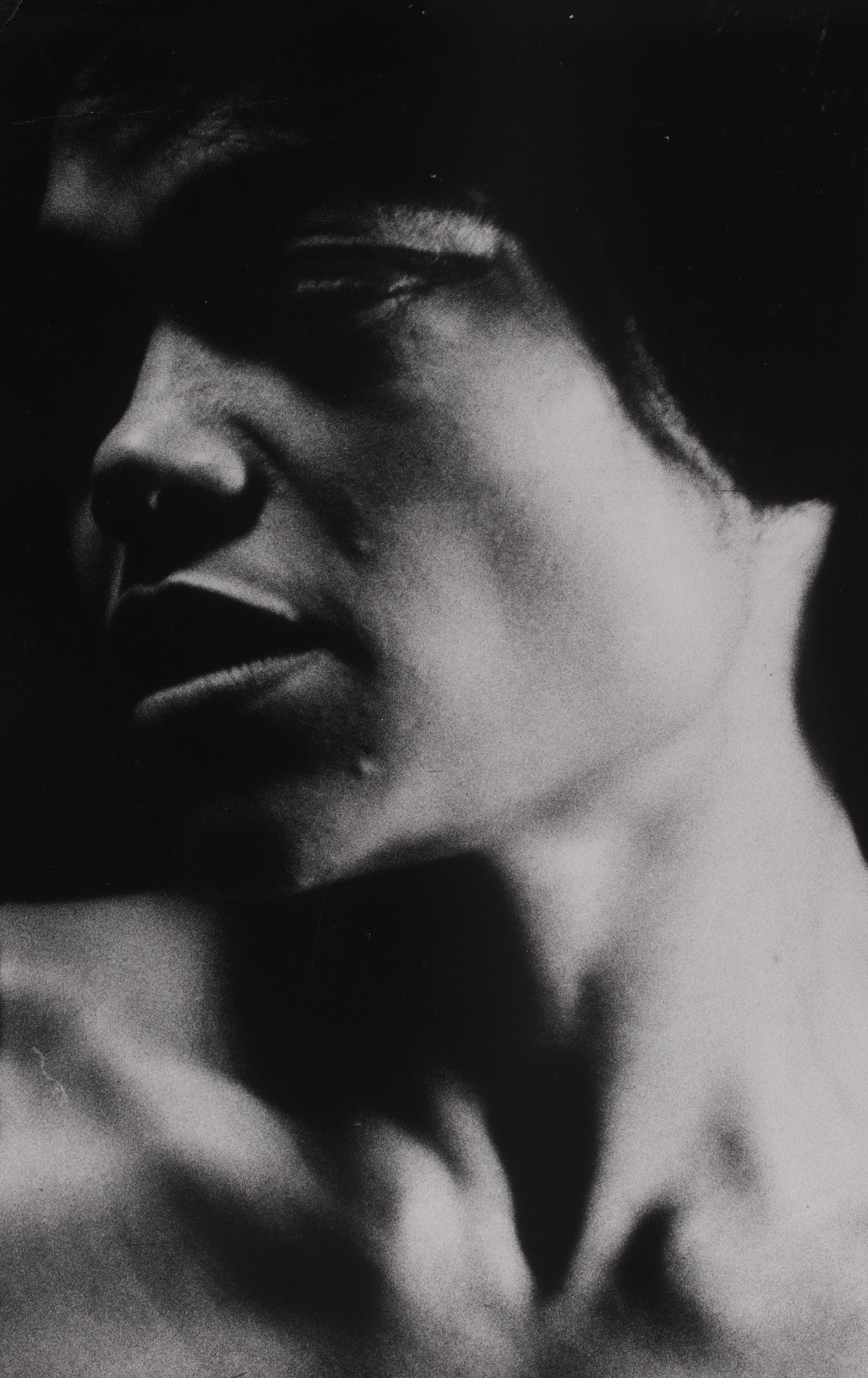

When a celebrity and a professional photographer collaborate, the portraits created can show us familiar faces as we are used to seeing them – or give us a little more. Portrait photography has been inextricably linked to celebrity culture up through the twentieth century, and the personal style of portrait photographers has taken on central importance too. Photographers will often strive to capture the character and personality of the person portrayed while employing his or her own signature style. Such distinctive aesthetics may reside in specific ways of using light and perspective or in the degree of staging employed.

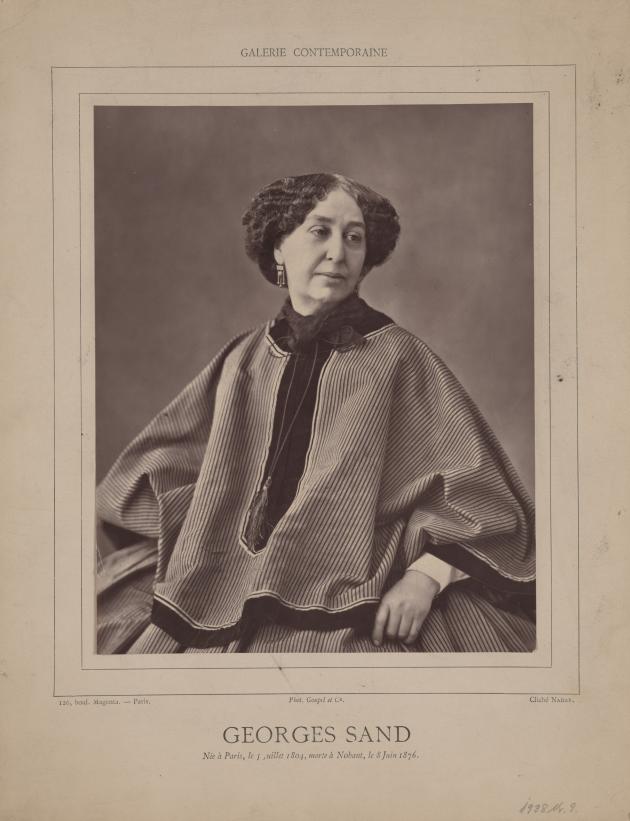

Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon)

Nadar was the most sought-after portrait photographer on the Paris art scene in the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike many other photographers of the period, he used neither props nor decorations, but let the sitter dominate the picture on their own. This lent a special intensity to his portraits of writers and artists of the time.

Photo: Nadar

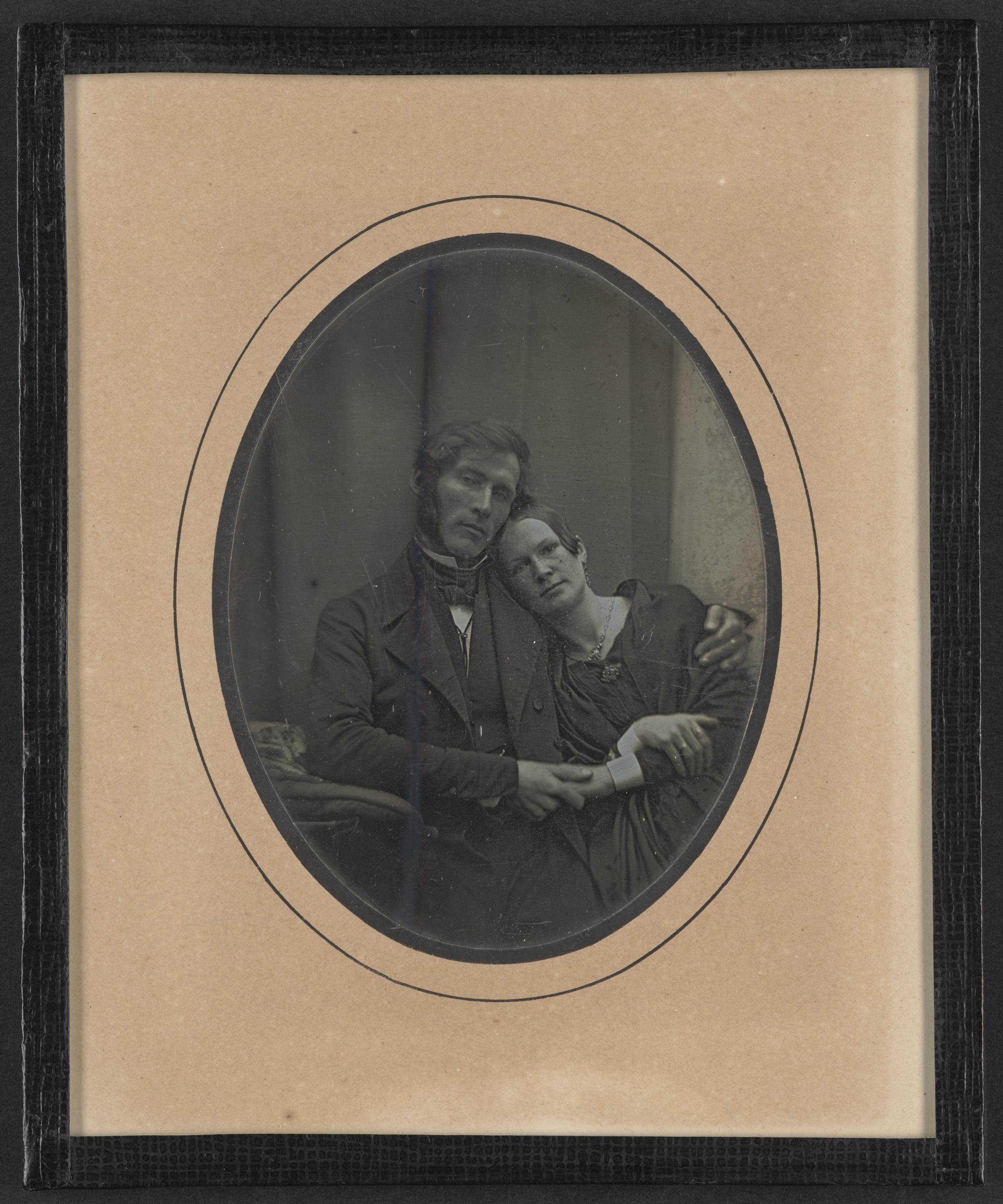

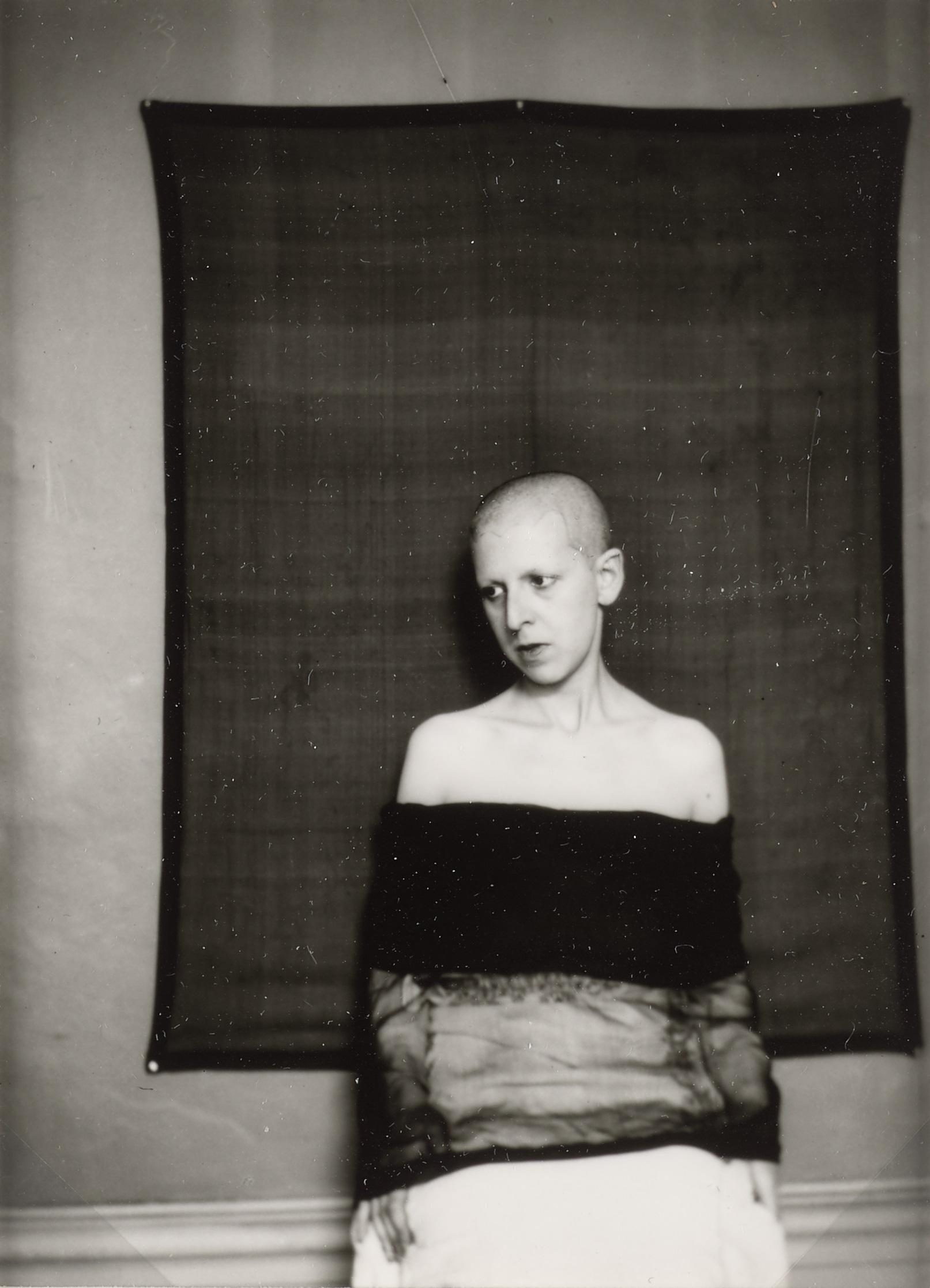

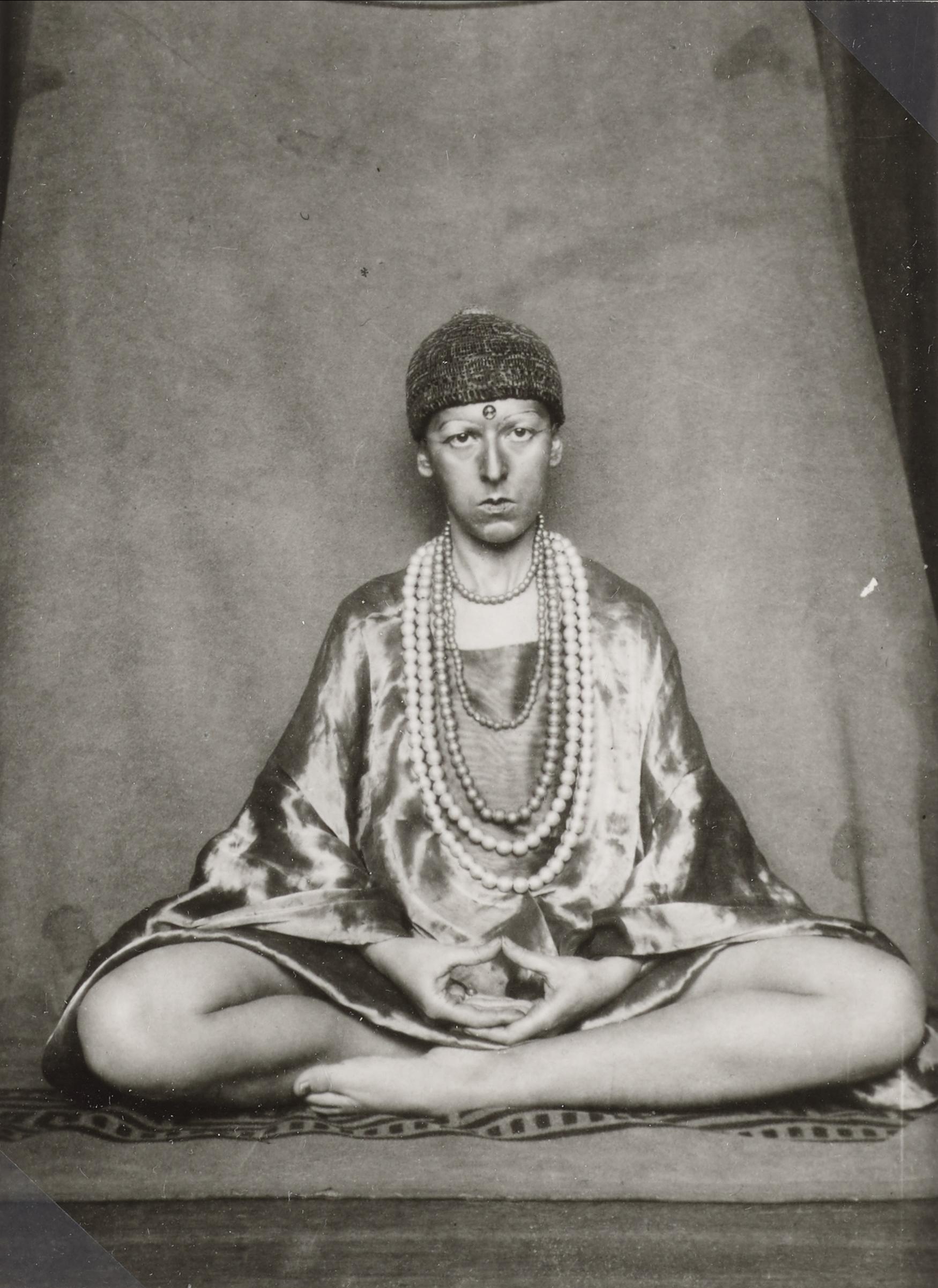

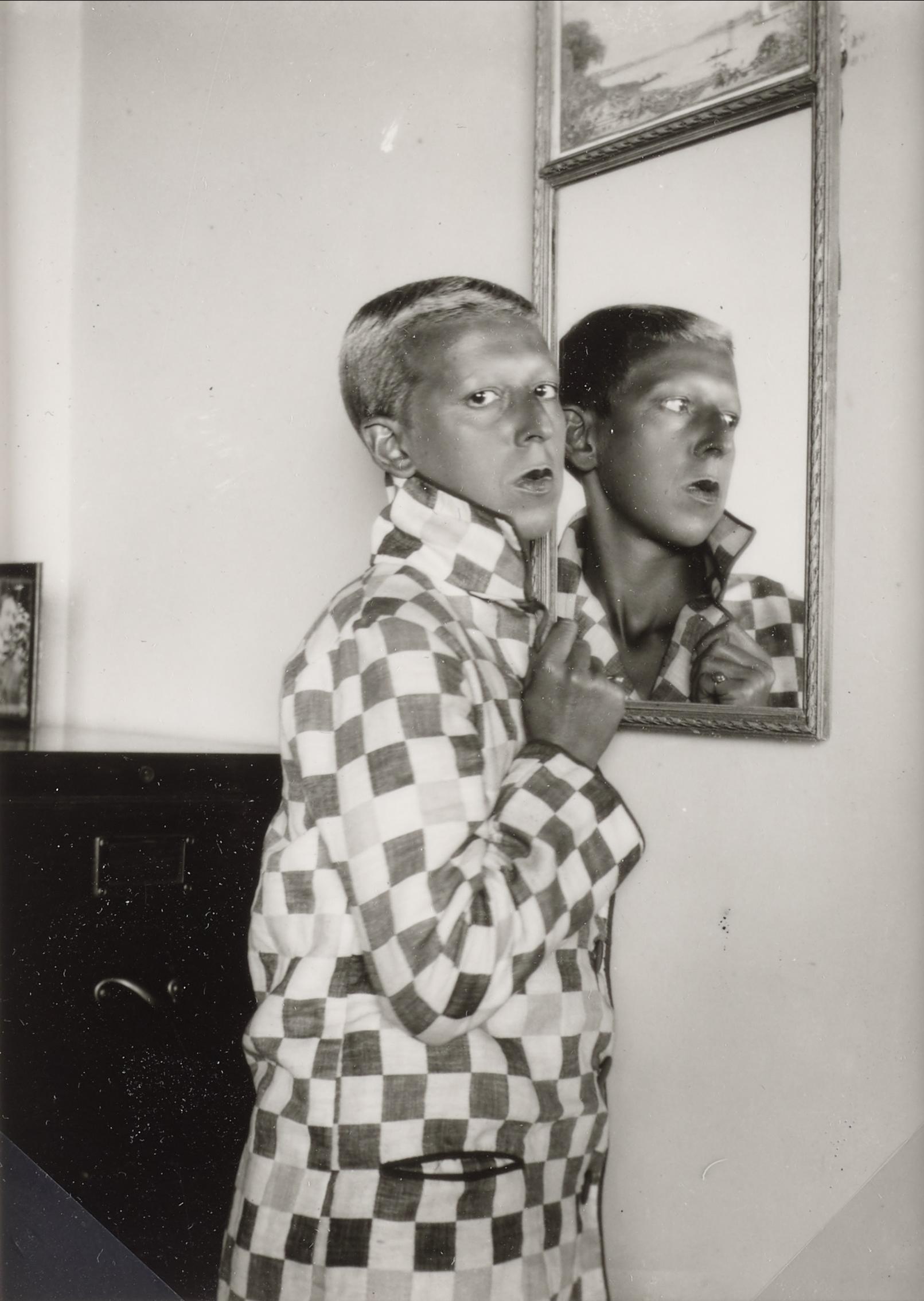

Claude Cahun (with Susanne Malherbe/ Marcel Moore)

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) and her partner Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe) created a large number of Surrealist self-portraits over the course of several decades, most of them in the 1920s and 1930s. During that period, they were also part of the Surrealist circle in Paris. Claude Cahun posed in front of the camera, and together the couple used costumes and role-playing to explore issues of identity and gender.