Anniversary article: The Black Diamond's architecture

How does a Swedish architecture journalist view The Black Diamond and the building's role in the city? Journalist and author Mark Isitt investigates this in this first anniversary article.

Mirages

... sssshhhhhhhhlllllllaaaaaauuuuoooo-kak-kak-kak-kak-kak-kaaaaasssshhhhhhhrrrrrrrrraaaaannnnnngggggguuuuuuuoooooooowch!

This sound... like a giant worm winding its way across the sand-coloured carpet and between the legs of the black office chairs... a hiss, followed by banging sounds that turn into a thump and then a frenetic flack-flack-flack-flack-flack, like a clattering wheel of fortune in Tivoli... at the same time there is a bubbling sound in the distance, like when the neighbour flushes the toilet, or a dishwasher is emptied of water... drip-drip, drip-drip... the sound gets closer... and suddenly Godzilla crashes right through the glass facade.

This is my workplace, the large reading room on the first floor of The Black Diamond, every weekday when I am home in Copenhagen.

About the author

Mark Isitt (1966) is a Swedish award-winning journalist and author who has written about architecture and design since the 1980s. He is an architecture critic for Göteborgs-Posten and host and expert commentator for Sveriges Radio's Stadsinspektionen and the TV programmes Grand Designs (TV4) and Hemma hos arkitekten (SVT). He has written several books, including Förenta nationerna (Bokförlaget Max Ström, 2015) and Stockholm Sub (Frank Review, 2018) about the architecture of the metro. He lives in Copenhagen.

And every weekday, exactly at 1 p.m., the sound comes. Or the sounds, because I've probably heard about twenty different variations at this point. Small avant-garde cacophonies, as random as a piece by John Cage, but more compressed, rarely more than a minute long. But they do their job: ricocheting between the concrete walls, rushing around, bombarding the senses, signaling that now, now it's afternoon, now it's time to really work.

Like factory whistles from the old days.

How people in the room react depends on whether they have been here before. Newcomers sit tight, look around, try to locate the source of the sound, wiggle their heads like pigeons. While the rest of us calmly write on, pretending nothing happened, we the initiated, we who see ourselves as established. But behind our stone faces – pure happiness! For the thought alone, we are pleased that someone in the library management has gone to the trouble of ordering a series of works by a composer. A composer who, in turn, has gone to the trouble of composing these really bold, cinematic, magnificent, provocative, humourous, nimble, silly piccolo symphonies. That says most about the level of ambition here at "The Diamond".

And I haven't even mentioned the architecture yet.

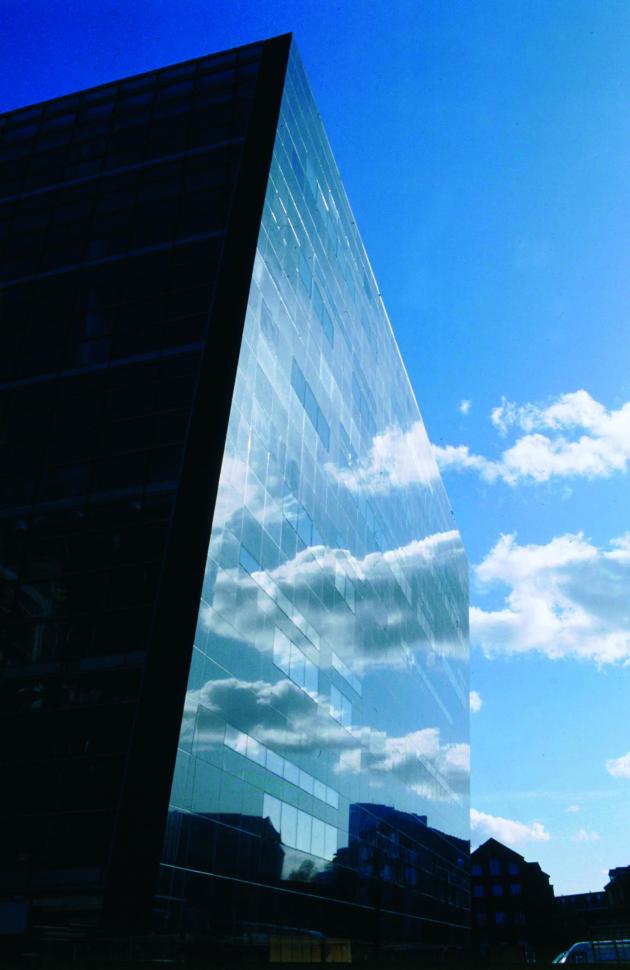

Deep black. Blacker than the Mandrake's cloak and just as illusory, so glossy that it seems white, transparent, abstract, like a mist. Especially next to Hans J. Holm's rustic original library from 1906, next to Børsen and the National Archives and Christiansborg. Fragile like a mirage. A simile that is actually more relevant than one might think, at least for a Swedish architecture reviewer who is used to public projects rarely coming to fruition, voted down by the public, no matter how socially useful or architecturally excellent they are. But here, just a five-minute bridge ride from Sweden, the visions become reality.

24 metres high, 40 metres wide, 80 metres long, eight floors, 40,000 square metres, 4.6 million books (including a Gutenberg Bible, which the Danes cheated Sweden out of during the Great Nordic War in the early 1700s - give it back now! ), 14,000 square metres of exhibition space, a concert hall for classical orchestras, a café where I order a cappuccino and bun smeared with butter and cheese for breakfast and cappuccino and sourdough bread with potato, parsley pesto and North Sea Cheese for lunch (every tenth coffee is free).

Photo: Malthe Ivarsson

The quiet of the reading room is the primary reason I'm here, spinning through the revolving doors as soon as they start turning at 08:00. But gliding up the 30-metre-long escalator, through the 25-metre-high atrium, between the undulating mezzanine levels, with Per Kirkeby's 210 square metre ceiling painting as a backdrop – it's like stepping (sorry, rolling) into a parallel universe. An escalator that, it seems to me, is a seamless extension of the straight stretch that begins far away at Christiansborg and cuts through the historic Library Garden, between beech hedges and century-old rhododendron bushes, through the carved oak doors of the original library and up the granite steps and between the tables in the old reading room and above the noisy traffic of Christians Brygge, before it slides down the escalator and – kapow! – throws itself out through the prismatic glass section.

A bridge between yesterday and today. And tomorrow. Because precisely this is one of the most positive effects of The Black Diamond - which we can all enjoy, regardless of where in Denmark we are - the building's redemptive influence on Danish architecture. This is the building that paved the way for the icons, for the Opera and the Royal Danish Playhouse and BLOX and DR Koncerthus and The Blue Planet and whatever they are called. And this is the building that started the rebellion against the previously smooth aesthetic. It may not be so easy to see at first glance, but if you stand on Søren Kierkegaards Plads, you see how the cube works, as if it is about to stand on its head, as if it is about to take a leap and make a belly splash straight into the harbour – plop! - as if it had started all the way from Christiansborg, but regretted it just before the jump. Not at all the strictly perpendicular architecture that previous generations preferred.

It is a stubborn attitude that is also felt inside, in the crooked and undulating walls, in Kirkeby's colour explosion. But also in the handling of materials, the heavy concrete that boldly collides with frosted glass. In rubber, black and thick, which adorns counters and railings. And in the atrium's almost surreally reduced colour palette, black and white, as graphically clear as a Pop Art work. And, speaking of art, if you go to the top, to the eighth floor of the building, you will see how the parallel escalators are crossed by a diagonal bridge, while also extending over a circular descent to the basement level. A suprematist Malevich painting in three dimensions.

With this said, we are not talking about bold experiments with form. (When I interviewed Daniel Libeskind, who designed the Jewish Museum, located in the northern corner of the old library—a building where there is hardly a right angle—he criticised the Diamond for being “too cautious.”) But now it is also "The Royal". The building was inaugurated by Queen Margrethe II on September 9, 1999. In other words, if this were antiquity, Plato and Socrates would have been hanging out here, striding up the escalator in their woolen togas and cowhide sandals. And in the Renaissance, Leonardo and Michelangelo would have stood and leafed through the Gutenberg Bible (and probably also thought it was "too careful"). This is a city of knowledge. What might sound as if the building's primary purpose is to protect the treasures - this is how the Holm building appears like an Ivanhoe fortress - but the Diamond manages to be both heavy like a safe, stable like Kaba and at the same time flirtatious and seductive.

Which is felt in the reading room. If you come after nine, the office chairs are usually occupied, and you are the one who must sit in one of the Poul Kjærholm chairs in natural leather along one of the short sides.

Terrible fate!

Mark Isitt

Reading room, Black Diamond, 21 October 2023