Monitored and recognised

The police used photographs early in their work. Today, we are all photographed daily by surveillance cameras.

We are photographed by surveillance cameras many times every day. And corporations are developing face recognition software that can identify us in pictures.

The police were the first to develop ID photography for criminals. Some even developed theories claiming that certain facial features were particularly associated with crime and tried to prove it with photographs.

Today we have legislation to ensure we are not tracked everywhere. Many people are sceptical of surveillance and registration, and several artists address the issue in their own photographs.

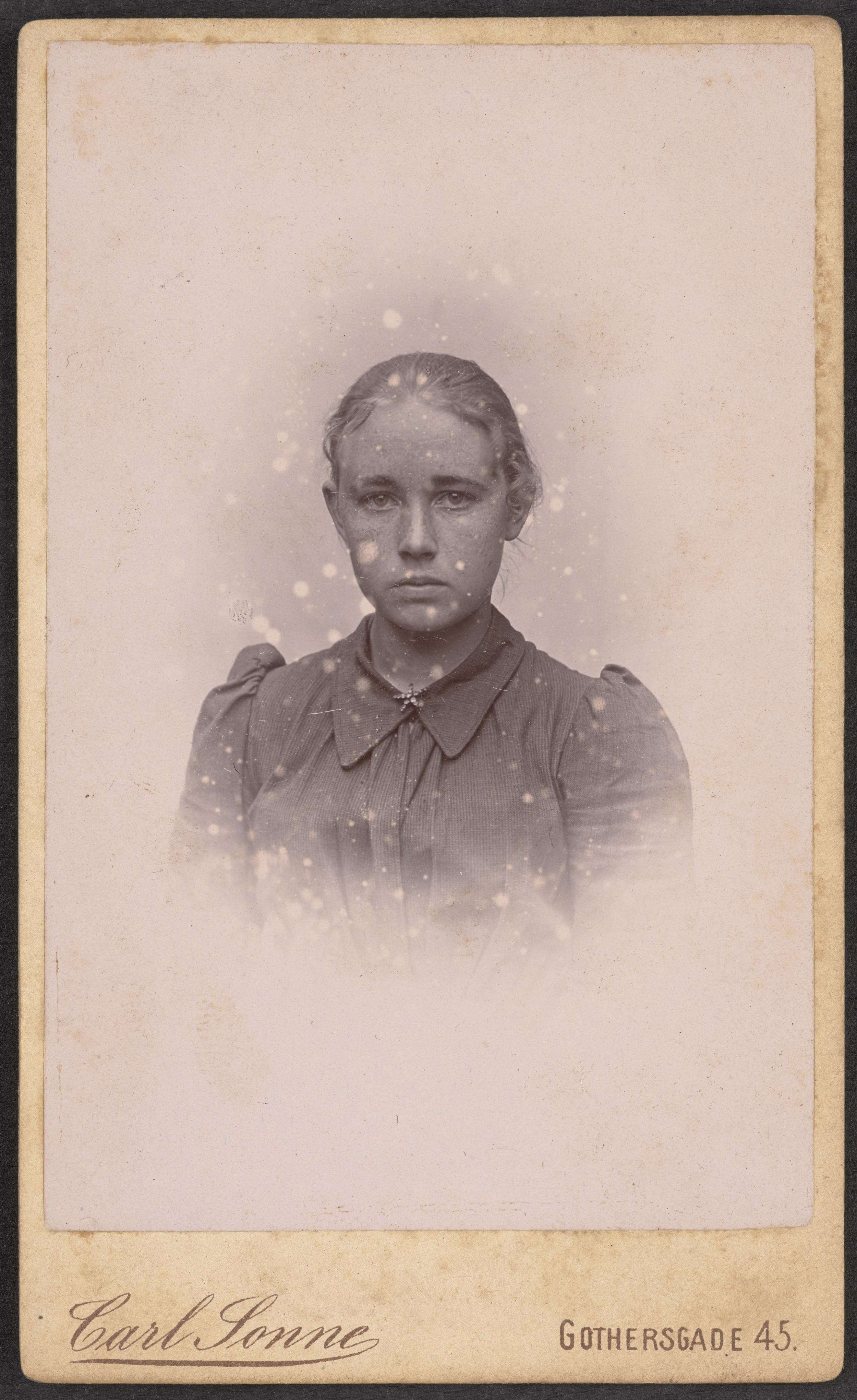

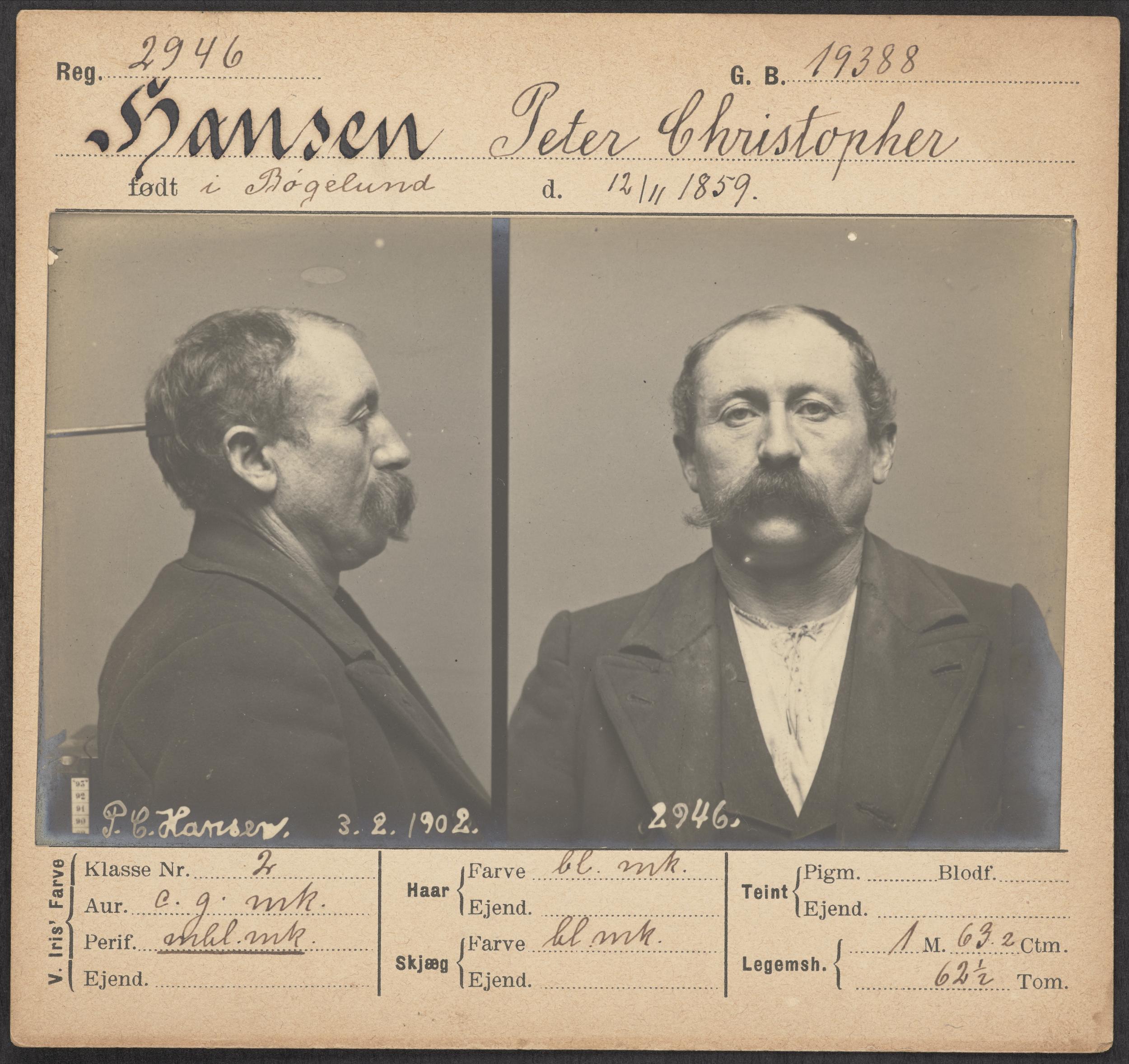

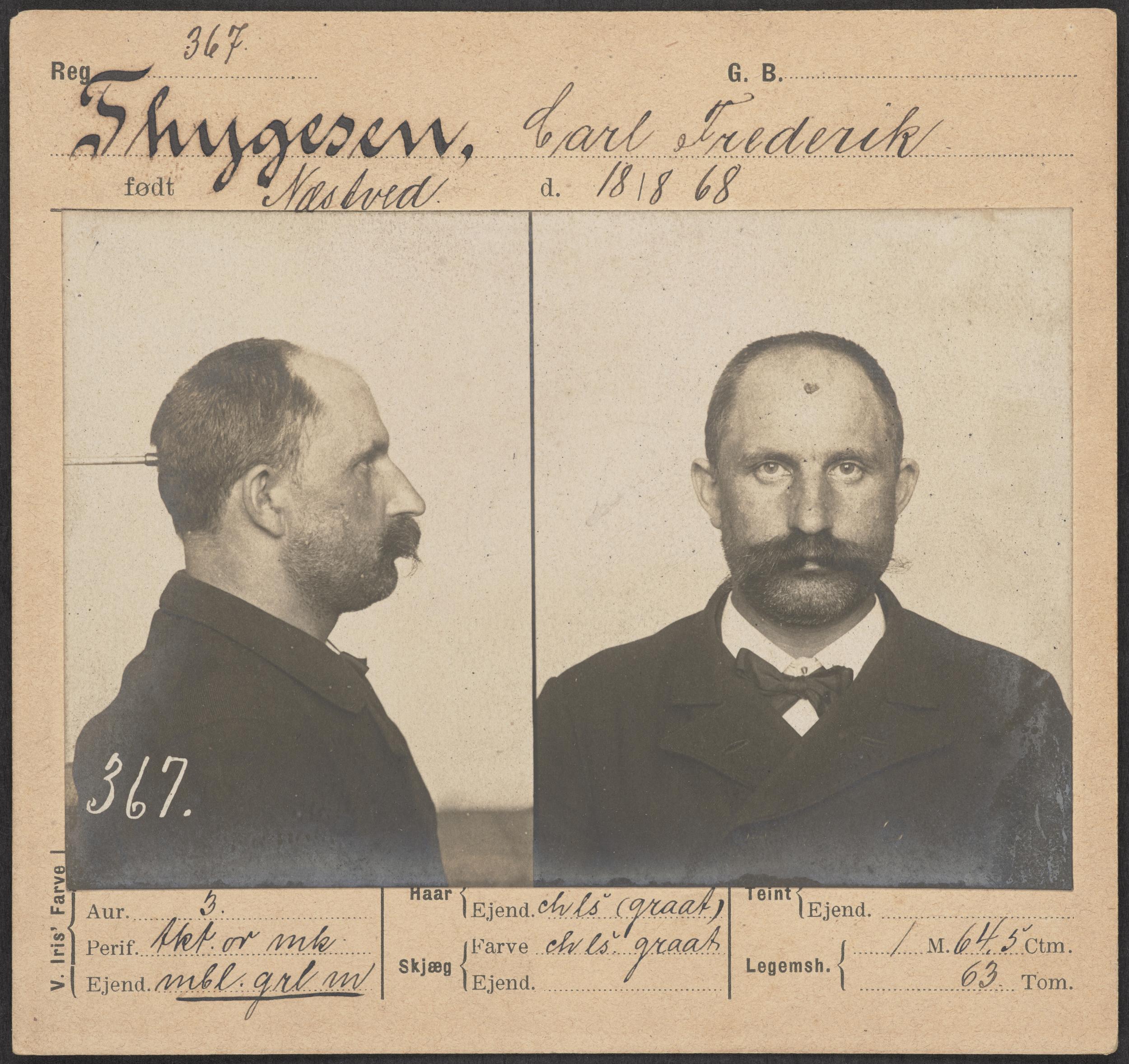

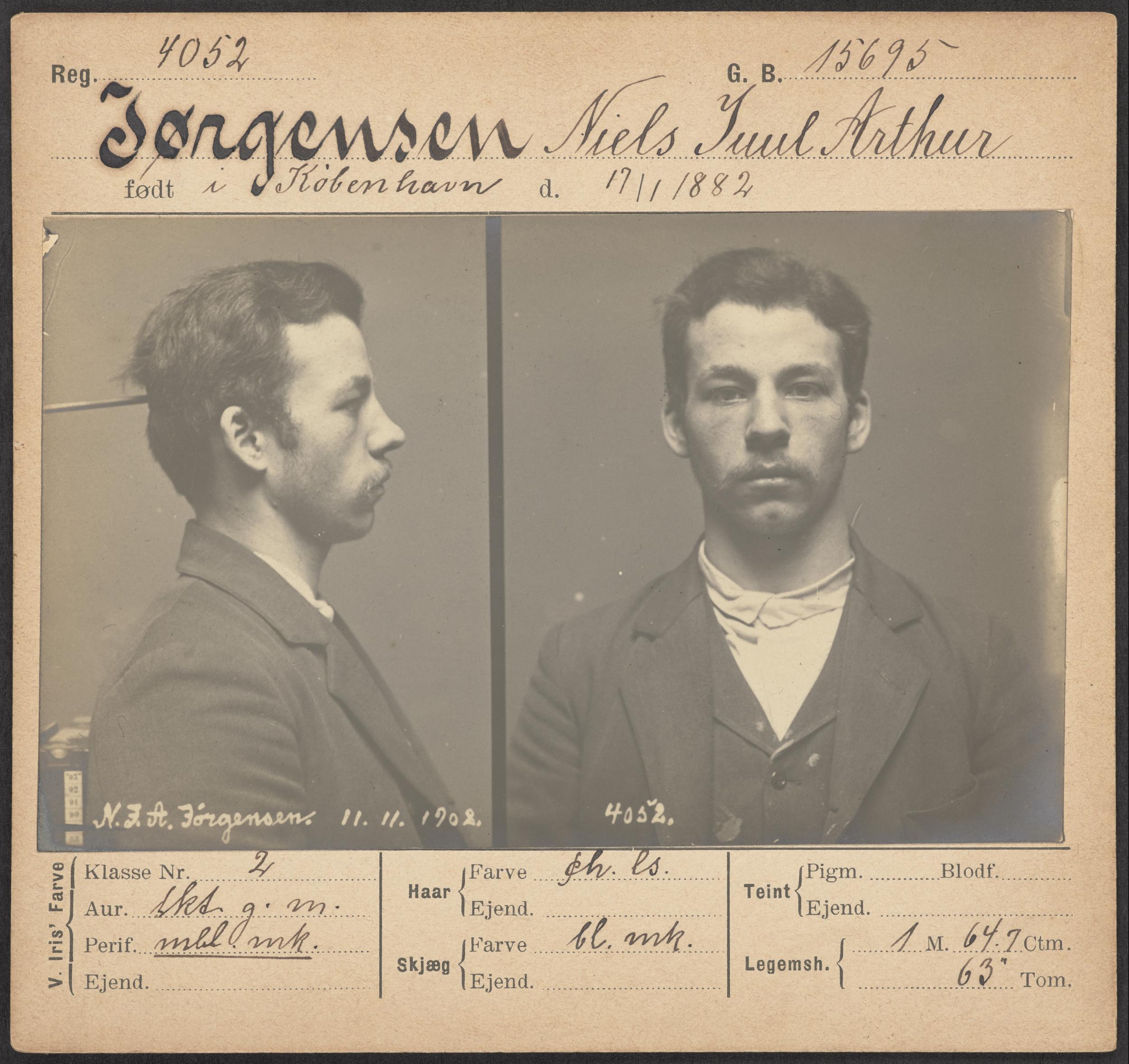

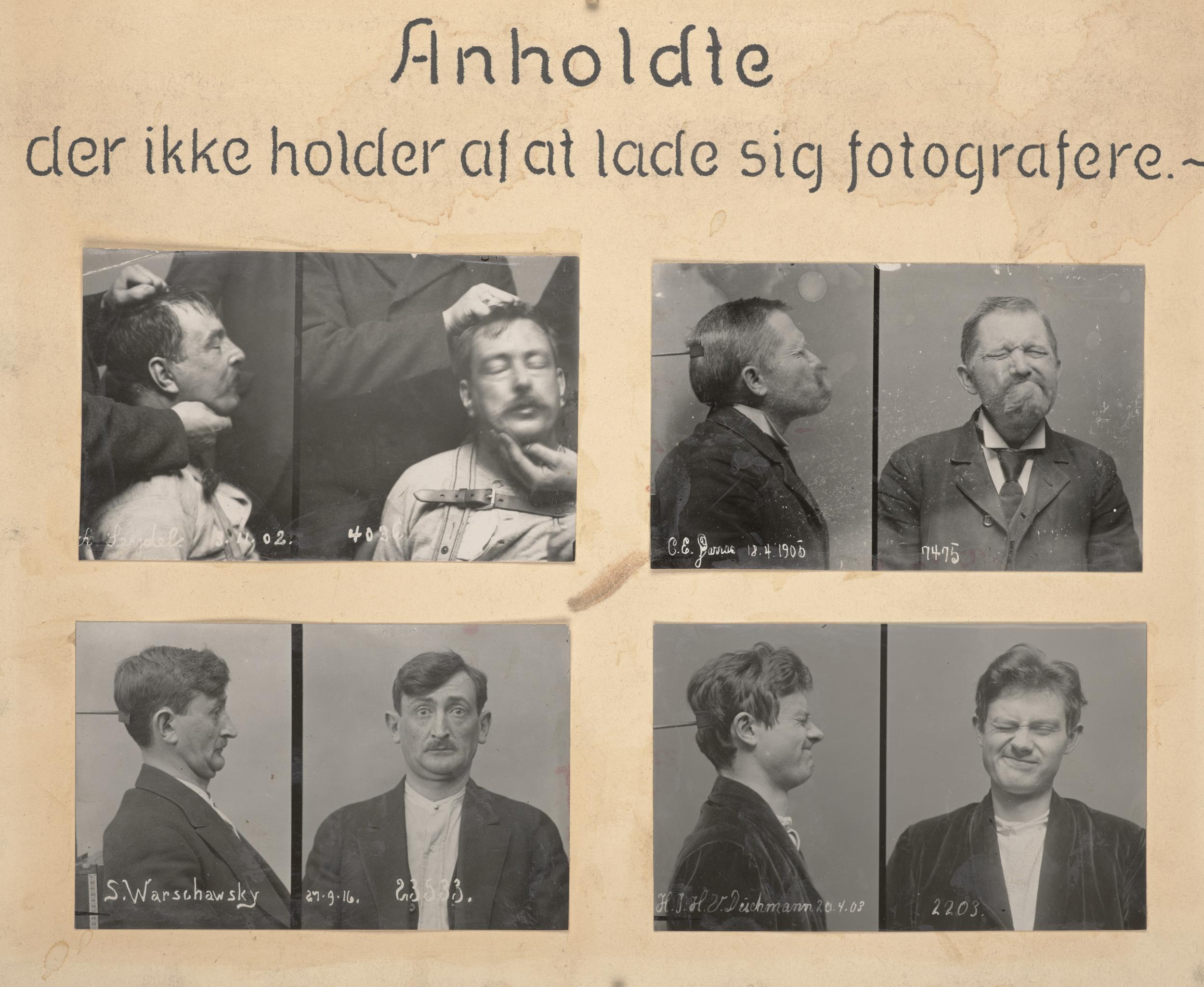

Police introduces photo ID in the 1860s

In Denmark, the police began taking portrait photos of criminals in the 1860s. At first, the pictures were taken in the portrait photographers’ studios and were very much like the full-length carte de visite photos prevalent in the period. The authorities later switched to close ups en face and in profile, inspired by the Parisian police offer Alphonse Bertillon. The photographs shown here ended up in the library collections because they were handed over by the Danish National Archives and the former Danish Museum of Crime.

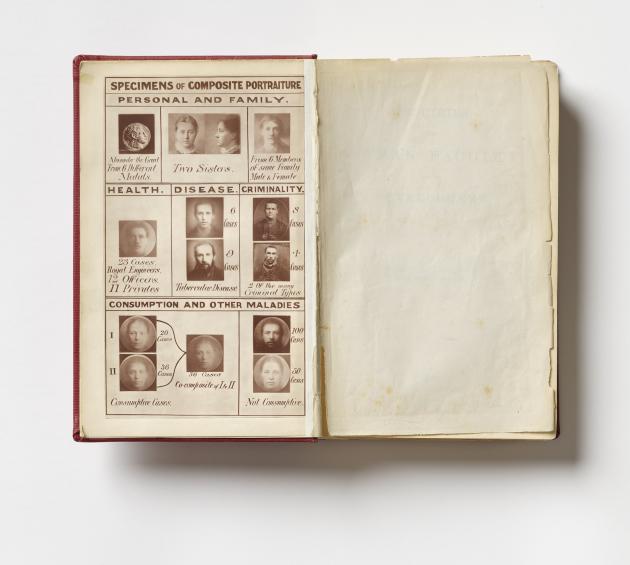

Nineteenth century theories of criminal facial features

In nineteenth-century Britain, Sir Francis Galton developed a theory of heredity which included the notion that criminals had distinctive facial features. He used photography to try to prove it. By exposing negatives depicting different people onto the same piece of paper, he believed himself able to illustrate that, for example, a broad jaw was typical of criminals.

Photo: Anders Sune Berg

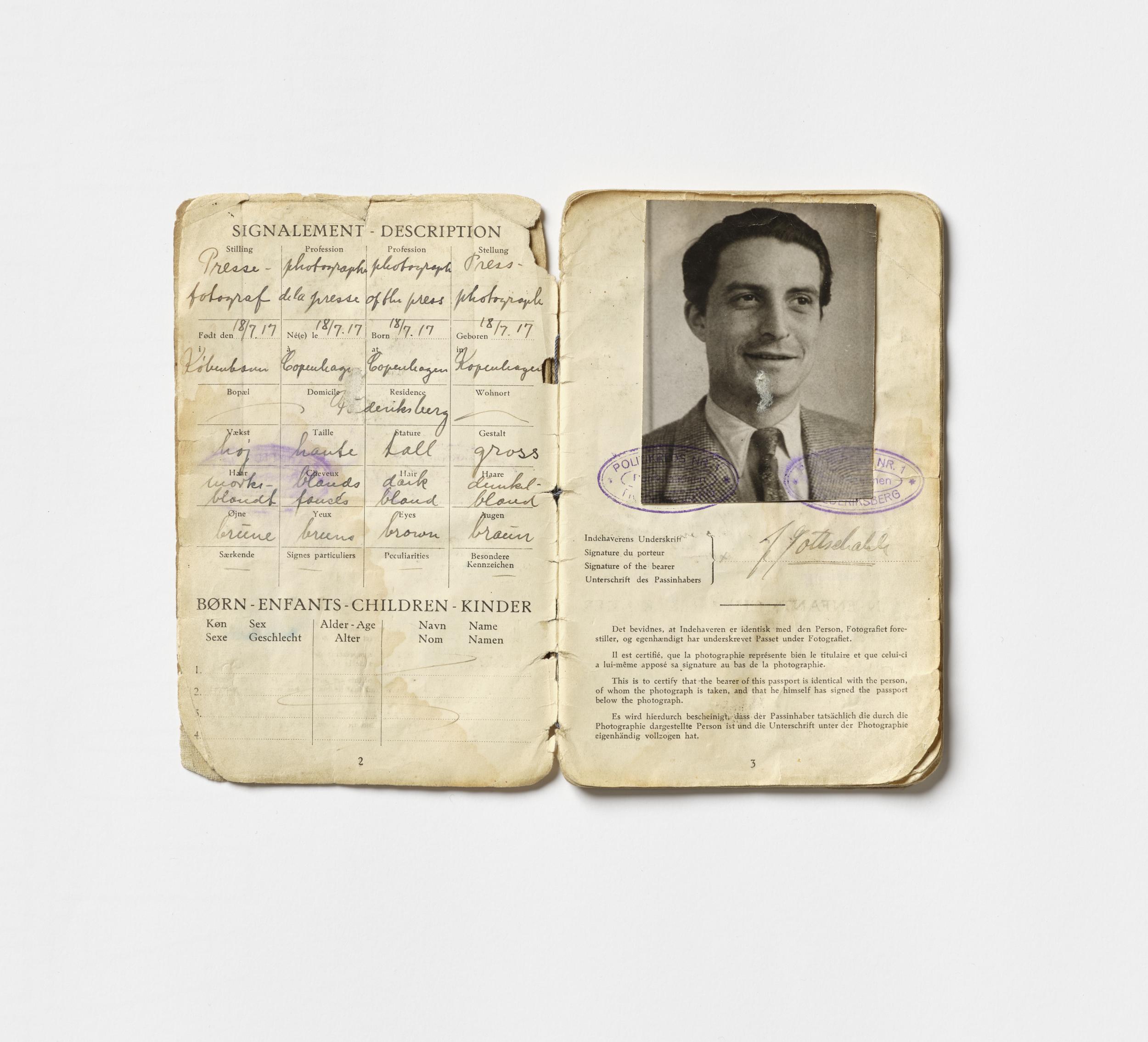

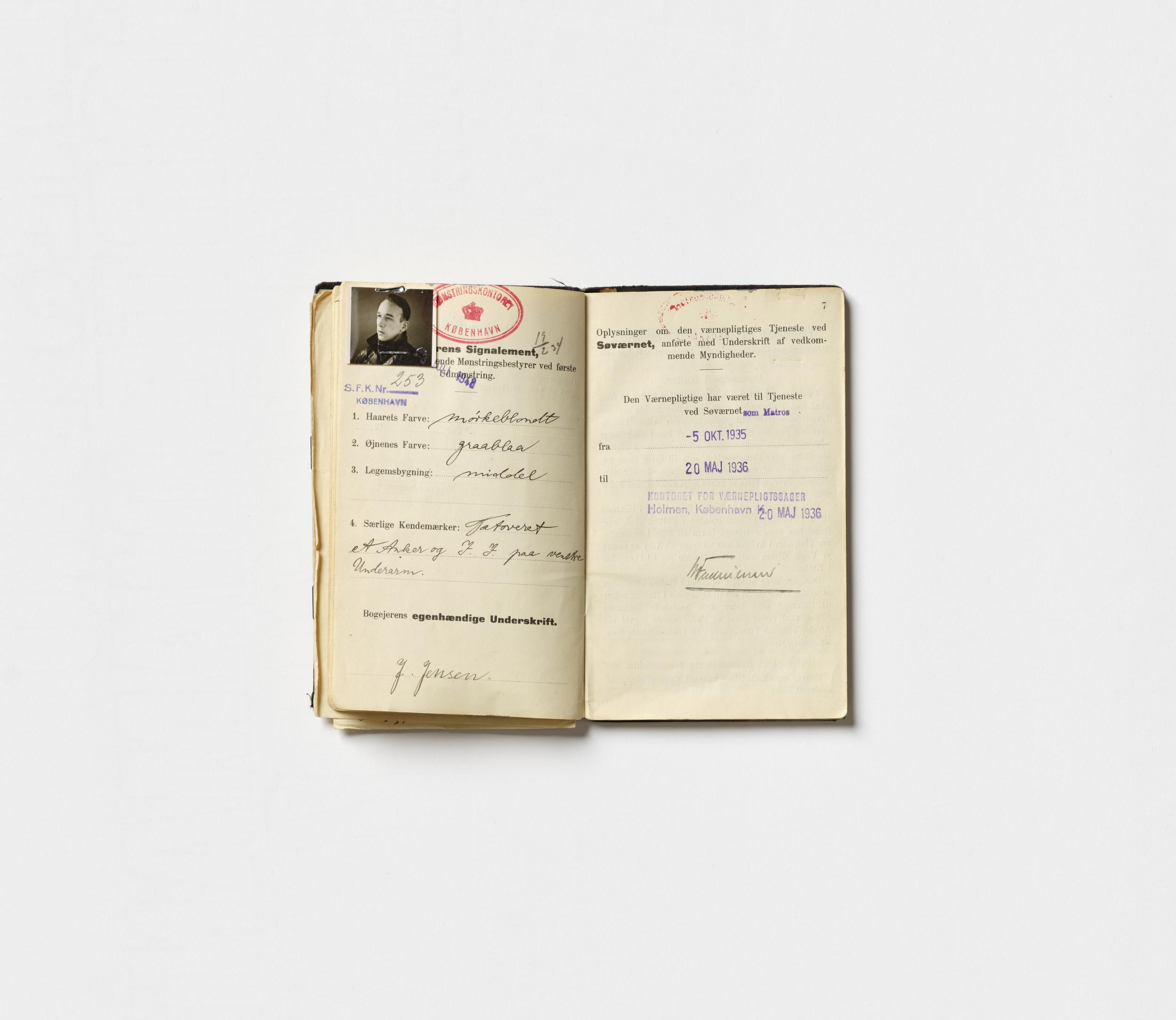

Photos in passports and other ID

The practice of having photos in passports began in the 1920s. The photograph was intended to assist identification and help control people’s movements across national borders. Photographers made money from taking multiple small portraits, and photo booths offered the same service. Today, photographs are still used for identification. At the airport, this is done by means of face recognition software, and photographs are used in conjunction with iris and fingerprint scans.

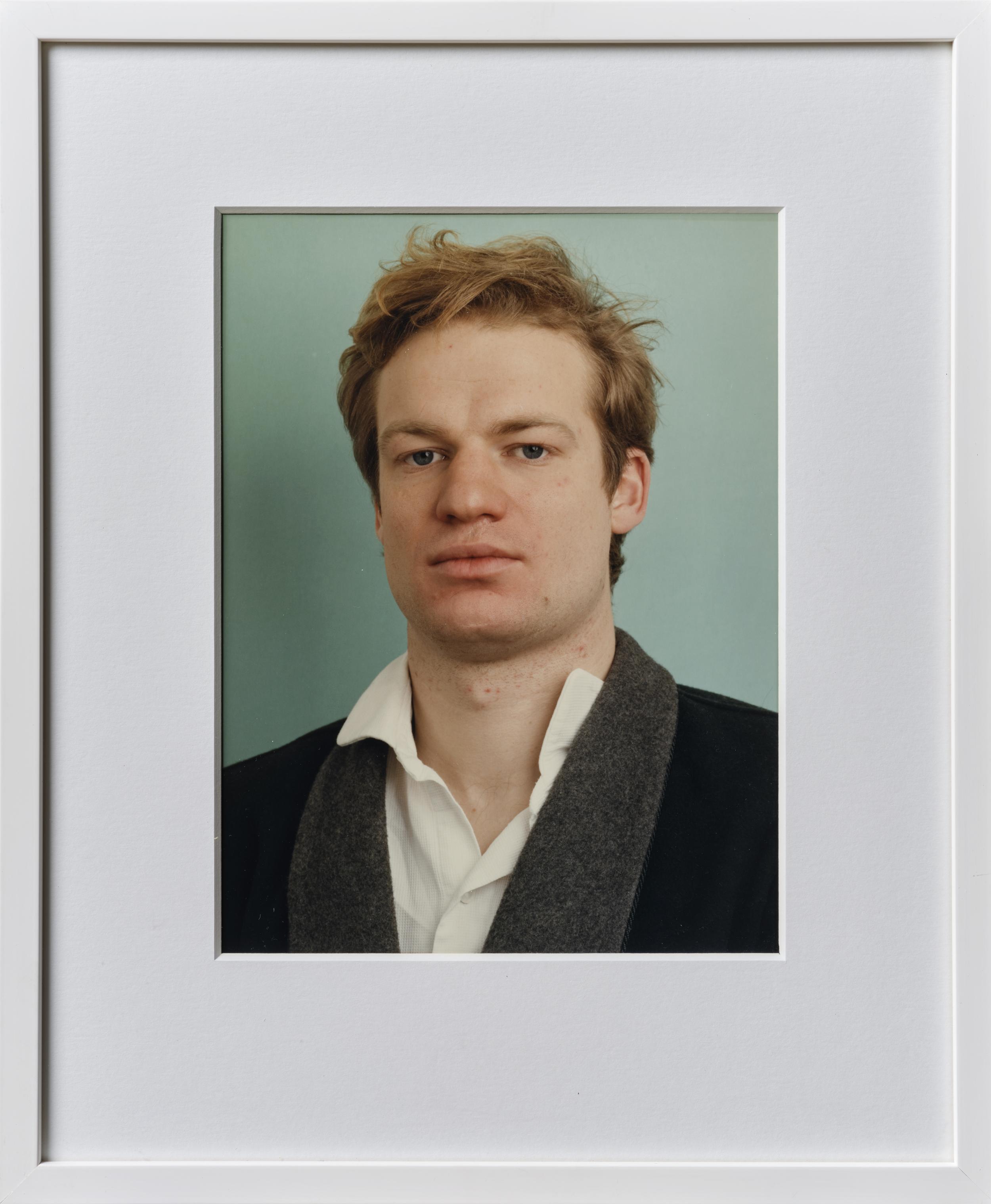

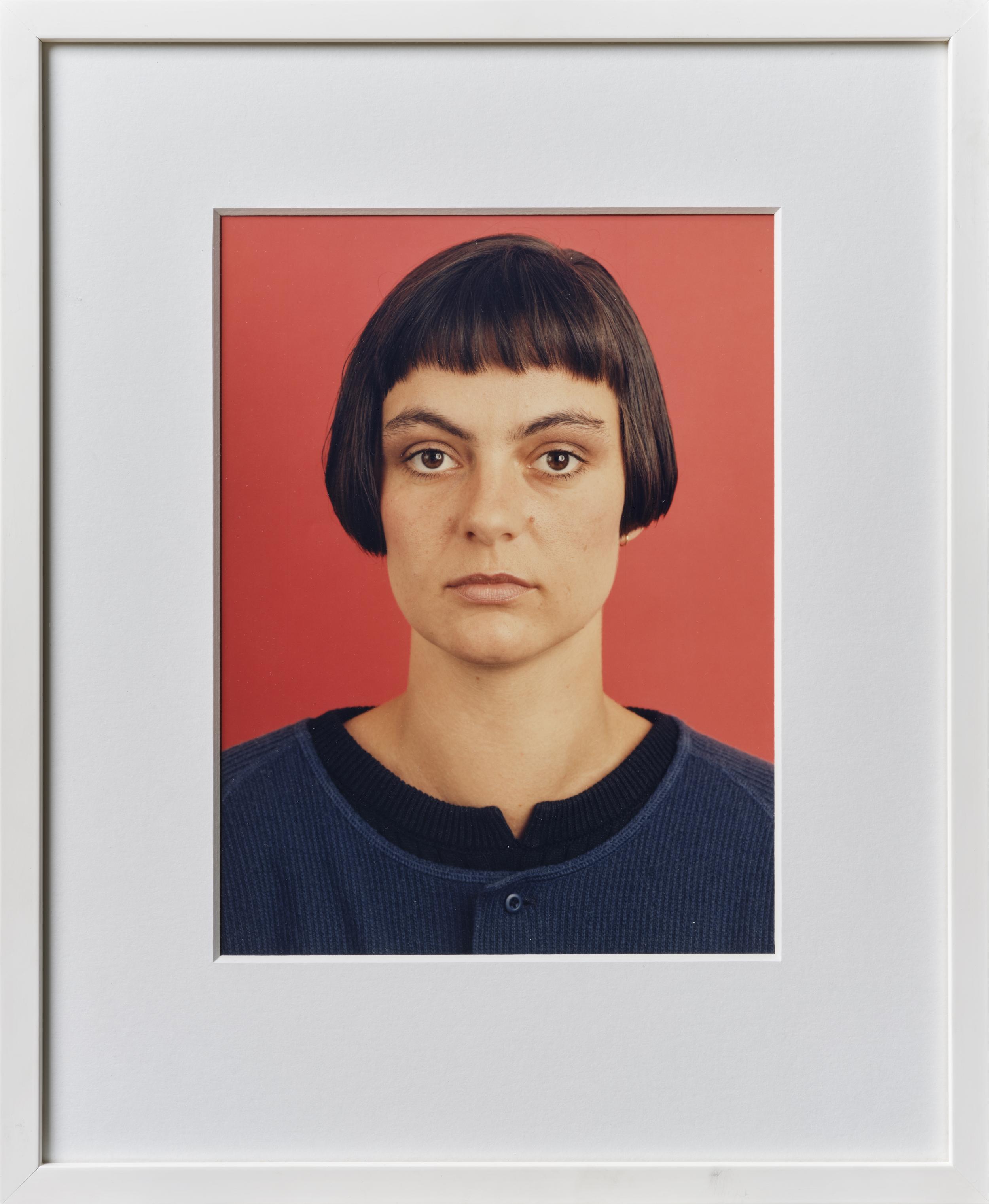

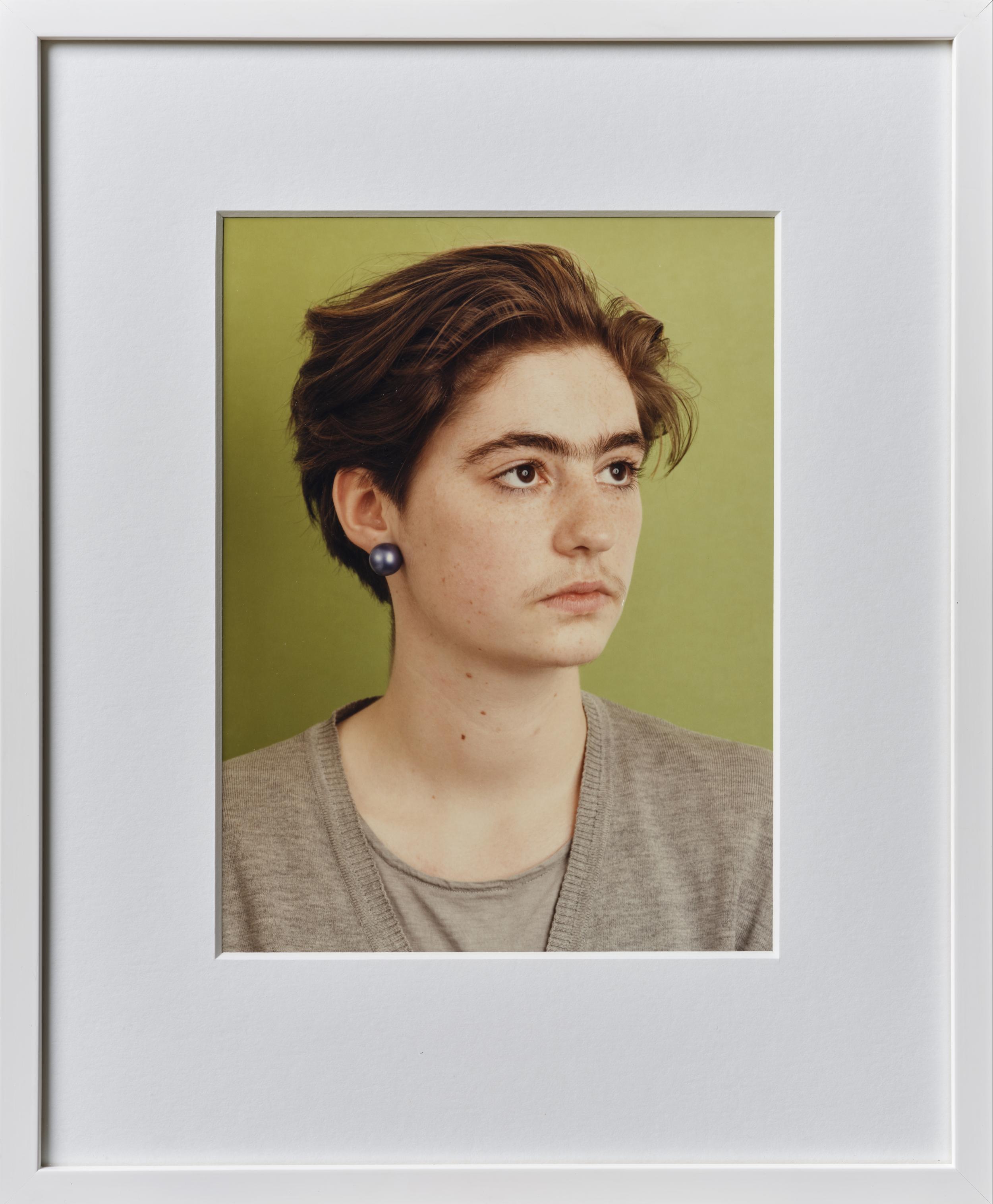

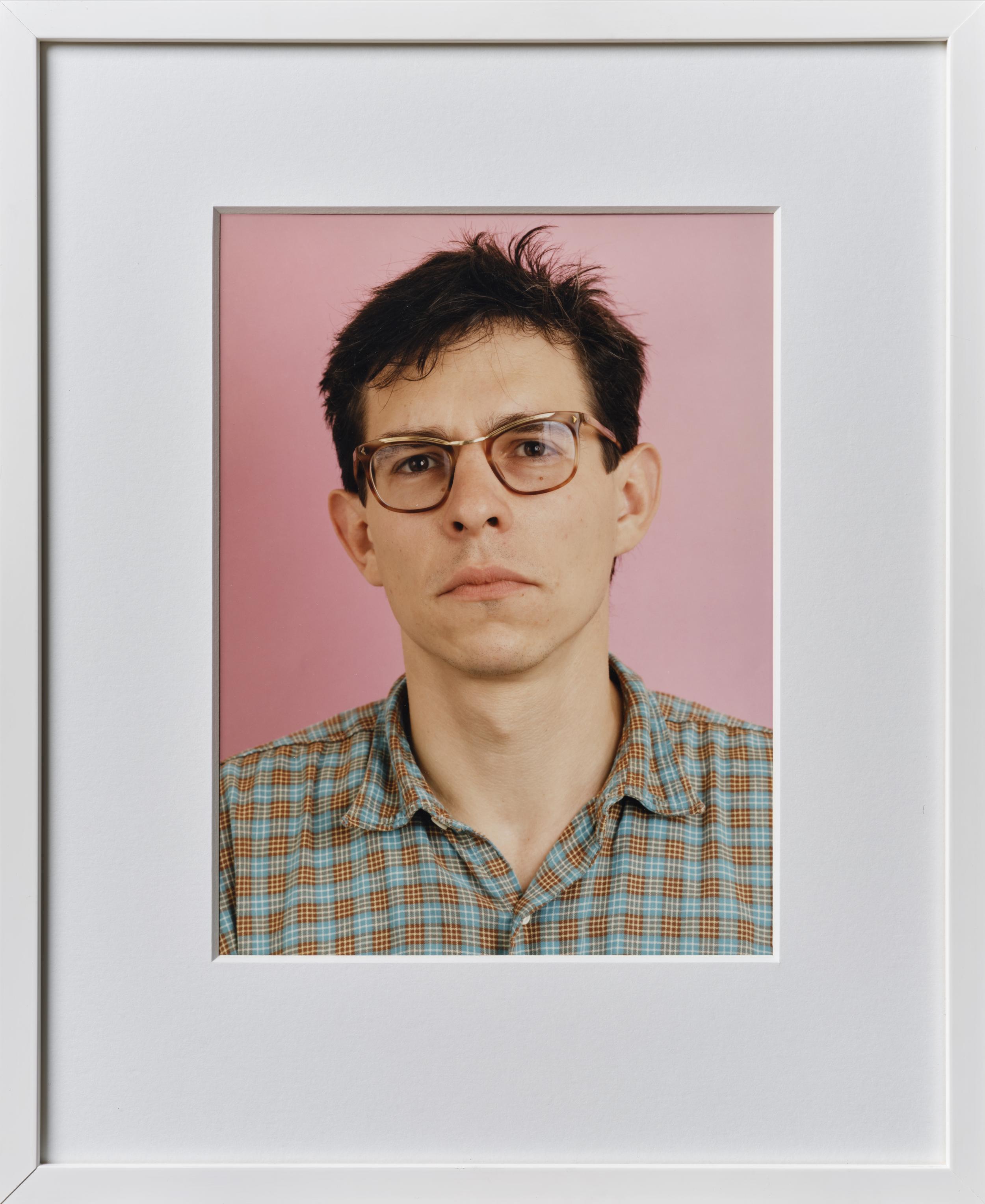

Thomas Ruff

While studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf, Thomas Ruff photographed people looking expressionlessly into the camera. Reminiscent of ID photographs, these pictures offered an alternative angle on portrait photography as a genre generally expected to express emotions and personality. At the same time, the works also had connections to police registration processes, with Ruff specifically pointing to German police activities during the Rote Arme Fraktion period in the 1970s.

Charlotte Haslund-Christensen

In Denmark, homosexuality was illegal until 1933, certainly for men, who were at risk of being arrested and registered by the police. This was the basis of Charlotte Haslund-Christensen’s work. During the World Outgames event in 2009, she invited LGBTI+ people to be photographed at the Police Station in Copenhagen. Participants had to take off their jewellery and have their fingerprints taken, thereby gaining direct, personal insight into what might have happened to them in Denmark back in the day – or in some of the countries where being LGBTI+ is still considered a crime today.

Peter Funch

For nine years, from 2007 to 2016, Peter Funch took photographs on the same street corner in New York. In his series, certain people appear several times in different photographs. The works bring to mind the automatic recordings of surveillance cameras in public places, an impression supported by the titles, which indicate the place and time when each photograph was taken. But unlike the pixelated images produced by surveillance cameras, Funch’s images are crisp and sharp, and when exhibited they paint a vivid picture of how we move through the city, many of us introverted with headphones on and a cup of coffee in hand.